I grew up singing Bach hymns before dinner. We were all terrible singers, but it didn’t matter: my mother trained us to sing in parts. Children, adults and even teenage boys would toil our way through “Now Thank We All Our God.” My mother wasn’t interested in musical quality, but in the virtues of complexity and genius.

I grew up singing Bach hymns before dinner. We were all terrible singers, but it didn’t matter: my mother trained us to sing in parts. Children, adults and even teenage boys would toil our way through “Now Thank We All Our God.” My mother wasn’t interested in musical quality, but in the virtues of complexity and genius.

My mother is a writer, and it was always enormously clear to us that the focus of her passionate life was her study – no June Cleaver, she merely tolerated the kitchen. She had started her married life with no knowledge of cooking whatsoever, doggedly making her way through The Joy of Cooking, which combined the dubious pleasures of simplicity with – well – simplicity. She made the Joy’s recipes a bit more complex by eschewing white sugar and white flour and sprinkling wheat germ where possible. The goal was not an aesthetic one, any more than our Bach choral performances were.

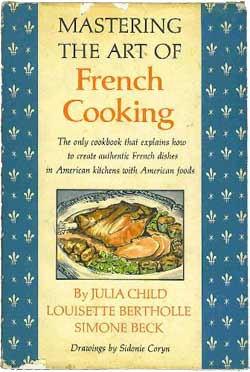

But during Christmas she would put aside her battered Joy of Cooking and take out that homage to fine cuisine, Julia Child’s 1967 Mastering the Art of French Cooking. She had the same two-volume set as did Julie Powell’s mother, with a cover, in Powell’s description, “spangled with tomato-colored fleurs-de-lys.” In Julie & Julia, Powell calls the recipes “incantatory.” They were that, and fiendishly difficult too. Perfect, from my mother’s point-of-view, for important days. For a normal dinner, we might eat spaghetti, but Christmas had to be marked by true effort and a gesture toward culinary genius.

One of my favorite memories is the year that she made a Bûche de Noël for Christmas. Given our bean sprout infected household, I was wildly interested in anything that combined sugar and chocolate – especially white sugar. Only those who grew up in a household that banned sweets can appreciate fierce deliciousness of crystalline grains of white sugar, the way they melt instantly and taste blissfully unhealthy.

My mother worked on that Christmas log all day. I distinctly remember her swearing as the clumsy, odd-looking cake cracked as she rolled it. We pasted in the holes with chocolate icing. Then we carefully created a stump at the top. With a fork we drew wavy lines to simulate bark, turning the cracked bits into knots of wood.

My mother worked on that Christmas log all day. I distinctly remember her swearing as the clumsy, odd-looking cake cracked as she rolled it. We pasted in the holes with chocolate icing. Then we carefully created a stump at the top. With a fork we drew wavy lines to simulate bark, turning the cracked bits into knots of wood.

Finally, she made mushrooms from meringue. Once baked, they looked rather lopsided, slightly odd, and yet undeniably mushroom-like. Having made more than we needed, we studded the whole log with mushrooms; they looked like type-writer keys sprouting from the trunk. I thought it was the most gorgeous, celebratory cake that had ever been made.

I am finishing this essay the day before I return home to be with my mother as she goes through home hospice. My sister summoned all my siblings yesterday, with the news that our mother had only weeks to live. Mom, she reported, seemed unsurprised by the doctor’s information. She lay down to read War and Peace, which — my sister added hopefully — “is a commitment of some size.”

But reading War and Peace for the tenth, or the twentieth, time is not a commitment to live longer — it’s a reflection of my mother’s way of living. She taught me that the important moments in life need to be understood, and then celebrated, with courage, the help of genius, and in the most intelligent, beautiful way that you possibly can.

My mother tells us that she plans to live until Christmas. She has a lot of Tolstoy to reread, and Chekhov waiting in the wings. So this year, I’m going to make the Bûche de Noël. I’ve already prepped my nine-year-old daughter on the intricacies of meringue mushrooms and frosting stumps. What’s more, though my siblings don’t know it, we’re going to gather all of our spouses, ex-spouses, and teenage children, and make our way through “Now Thank We All Our God.” This Christmas feels like an emphatic bit of punctuation – not only to the year, but to my life. It has reminded me that traditions are made, they don’t just appear. If I don’t turn my mother’s mushroom-studded Bûche de Noel and her carol-singing into a tradition, they will become nothing more than a memory. Traditions are guides to live by, and memories are nothing more than snapshots.

I would like my daughter to learn the same lesson that my mother taught me: the trio of Tolstoy, Bach and an annual Bûche de Noël is a perfect guide to life and its quieter brother, death.

New York Times bestselling author Mary Bly is a Shakespeare professor at

Fordham University. As Eloisa James, she writes historical romances for

Harper Collins. She is the daughter of writer Carol Bly and poet Robert

Bly.