Ah, we’re off once again to see the wizard, played by, in his newest incarnation, James Franco. Apparently, according to a recent story on NPR, there are 8 other Oz-related projects in the works, and I suspect that the reason for this recent surge in interest has to do with the boom in dystopian literature and film. The 1939 film adaptation of L. Frank Baum’s Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a dreamscape antidote to the Great Depression, The Hunger Games of its time, as its central character, the unsinkable Dorothy Gale, and her little dog, too, took off to have a series of adventures— only to be quite happy, at the end, in true Hollywood romance fashion, to return to the home that she was once so desperate to leave. Like Katniss Everdeen prepping for the opening ceremony on the eve of the hunger games, Dorothy cleaned up nicely at the Emerald City Beauty Salon, and like Katniss, Dorothy was plucky and brave.

Ah, we’re off once again to see the wizard, played by, in his newest incarnation, James Franco. Apparently, according to a recent story on NPR, there are 8 other Oz-related projects in the works, and I suspect that the reason for this recent surge in interest has to do with the boom in dystopian literature and film. The 1939 film adaptation of L. Frank Baum’s Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a dreamscape antidote to the Great Depression, The Hunger Games of its time, as its central character, the unsinkable Dorothy Gale, and her little dog, too, took off to have a series of adventures— only to be quite happy, at the end, in true Hollywood romance fashion, to return to the home that she was once so desperate to leave. Like Katniss Everdeen prepping for the opening ceremony on the eve of the hunger games, Dorothy cleaned up nicely at the Emerald City Beauty Salon, and like Katniss, Dorothy was plucky and brave.

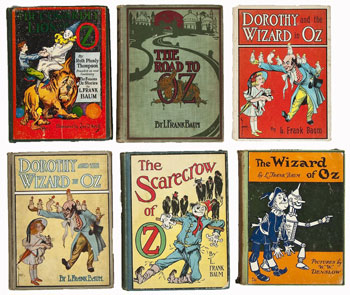

Unfortunately, Dorothy is what’s missing from Oz the Great and Terrible, for this is a prequel. And this version gives us something quite different: one part buddy film (the main buddy being a monkey—surely viewers can’t help but think of the 2011 Rise of the Planet of the Apes, in which Franco spent a good amount of time with a chimp), and one-part Updikian Witches of Eastwick. The 1939 MGM musical and the current film are, of course, only two among many adaptations, which began shortly after the novel’s publication in 1900. Baum himself wrote two versions for the stage. And when there are remakes and sequels, a blockbuster prequel is sure to follow, so this latest development shouldn’t surprise us. (There is a rumor of a sequel to this prequel— let’s not go down that yellow-brick road for now).

But really, trying to tell the story of Oz without Dorothy seems somehow beside the point. If we want to read this movie metaphorically, we might think about it as symbol of the treatment of women in films in general, but a funny thing happens on the way to the Emerald City: Dorothy’s absence becomes a palpable presence, much like that of the title character in Daphne du Maurier’s and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca. The protagonist’s absence is certainly ironic, because critics have long pointed out the influence of strong women—in particular his aunt, Katharine Gray, and his mother-in-law, the suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage, on Baum’s writing.

But really, trying to tell the story of Oz without Dorothy seems somehow beside the point. If we want to read this movie metaphorically, we might think about it as symbol of the treatment of women in films in general, but a funny thing happens on the way to the Emerald City: Dorothy’s absence becomes a palpable presence, much like that of the title character in Daphne du Maurier’s and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca. The protagonist’s absence is certainly ironic, because critics have long pointed out the influence of strong women—in particular his aunt, Katharine Gray, and his mother-in-law, the suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage, on Baum’s writing.

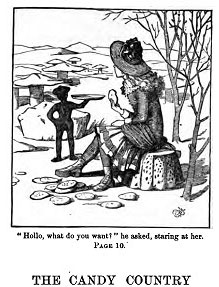

Even more ironic is that another quite probable resource for Baum was a short story by Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women and creator of the resilient and determined Jo March—a forerunner of Dorothy and Katniss. “The Candy County,” one of Alcott’s fairytales for children, was included in Lulu’s Library, Vol. 1 (1885/1886). It’s quite likely that Baum, who had a large collection of children’s books and who described his Oz series as fairy tales—he acknowledged the influence of the Grimm Brothers and Hans Christian Andersen—was familiar with Alcott’s work. Both Baum and Alcott, as well as Twain and Kipling, published work in Mary Mapes Dodge’s St. Nicholas Magazine. The similarities between Baum’s 1900 novel and Alcott’s earlier “Candy Country” are striking—and much closer than any comparisons to another source of inspiration, the Alice books. Alcott’s “Candy County” borrows from Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe but features at the center a willful and curious female child-protagonist.

The story begins with a young girl named Lily deciding to take her mother’s red sun-umbrella to school one day. When her nursemaid warns her that “the wind is very high. . . you’ll be blown away,” Lily replies, “I wish it would; I always wanted to go up in a balloon.” A short while later, her dream comes true: “a gale of wind nearly took the umbrella out of her hand. She clutched it fast; and away she went like a thistledown.” Eventually, she loses the umbrella, and “fell down, down, till she went crash into a tree which grew in such a curious place that she forgot her fright as she sat looking about her, wondering what part of the world it could be.”

The story begins with a young girl named Lily deciding to take her mother’s red sun-umbrella to school one day. When her nursemaid warns her that “the wind is very high. . . you’ll be blown away,” Lily replies, “I wish it would; I always wanted to go up in a balloon.” A short while later, her dream comes true: “a gale of wind nearly took the umbrella out of her hand. She clutched it fast; and away she went like a thistledown.” Eventually, she loses the umbrella, and “fell down, down, till she went crash into a tree which grew in such a curious place that she forgot her fright as she sat looking about her, wondering what part of the world it could be.”

It’s Candy-land, inhabited by “sweet” “little people.” Eventually, Lily runs away to Cake-land, where she is taken in hand by a gingerbread man whose name is Ginger Snap and who only wants a soul (a block of condensed yeast, so that he may “rise. . . into the blessed land of bread”). Lily tags along to Bread-land, where she takes a class with a Professor of Grainiology, but then she realizes that she just wants to go home. This turns out to be fairly simple: she “wished three times to be in her own home, and like a flash she was there.” As in Baum’s novel, there is no suggestion that the fantastic journey was just a dream.

Saccharine, yes—but not a wizard or a frontier con man in sight. According to Edith Wharton, Alcott invented the American girl. Let’s hope that girl finds her way back soon.

Carolyn Foster Segal is an essayist and a teacher of creative writing at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, PA.