There is a basic tenet in Buddhism that the only reality is what is happening now. The past exists only in our heads, muddled by our own unavoidable perspectives and biases, and the future may or may not come to pass. If a piano falls on you in three seconds, it’s best not to have spent that time separated from the sights, sounds and emotions of the moment.

There is a basic tenet in Buddhism that the only reality is what is happening now. The past exists only in our heads, muddled by our own unavoidable perspectives and biases, and the future may or may not come to pass. If a piano falls on you in three seconds, it’s best not to have spent that time separated from the sights, sounds and emotions of the moment.

I find this a helpful construct for many reasons; I tend to be a ruminator and a worrier, frequently leaving the moist, fragrant air of a summer second to regret the actions of a remote January morning, or to fret over what might happen as the air grows crisp and the leaves turn from green to red. I wonder, though, if it is wrong to remember places I loved, that are forever lost to me, and that live on only in my memory and the collective memories of those who actually experienced them. It’s a moot point, really, because I can’t seem to stop myself, and it doesn’t seem to do me any significant harm to remember. This happens, particularly, when I think about my grandmothers’ houses, places that still exist, but which are empty of the people, the atmosphere and any other context that gave them meaning for me.

I have not seen the ocean in more than a year, and I feel keenly the inability to summon, clearly, the sound of waves on the sand, the salt smell in the air, and the sound of gulls. I know, though, that if I jettisoned my obligations, filled my trusty Hyundai with gas and started driving, I could be on the beach in less than 24 hours. I could feel the sand shift under my weight, search for shells and bits of glass, roll up my pant legs and flirt with the lacy white edge of ocean that rushed up to meet me. It’s all still there.

The house in which my mother grew up in Ohio is still there, too, but not really. 5105 Chestnut Avenue in Ashtabula Ohio, built on a red brick road, near the train tracks and a quick walk from the “downtown” where we shopped at Carlisle’s and went, after a Thanksgiving dinner with our Jewish family, to see the parade that brought Santa in for the season. A house built at the turn of the last century, divided into two parts with a series of mysterious tenants inhabiting the smaller, upstairs apartment that originally housed my great-grandmother. Two stern Mormon gentleman with suits on, a kind old lady who invited me upstairs and gave me candy, and a pair of white china swans made to hold bridge snacks. Inside, a foyer with a massive, embroidered chair that we believed to be a throne of some sort, always the smell of something wonderful cooking, the front bedroom with part of an ancient Cleveland Indians sticker on the mirror from when it was my uncles’ bedroom, the back bedroom filled with books, my grandmother’s bedroom redolent of perfume, her dresser covered with the jewelry, perfume and powder befitting a woman who had once been a model, and always been a beauty.

The house in which my mother grew up in Ohio is still there, too, but not really. 5105 Chestnut Avenue in Ashtabula Ohio, built on a red brick road, near the train tracks and a quick walk from the “downtown” where we shopped at Carlisle’s and went, after a Thanksgiving dinner with our Jewish family, to see the parade that brought Santa in for the season. A house built at the turn of the last century, divided into two parts with a series of mysterious tenants inhabiting the smaller, upstairs apartment that originally housed my great-grandmother. Two stern Mormon gentleman with suits on, a kind old lady who invited me upstairs and gave me candy, and a pair of white china swans made to hold bridge snacks. Inside, a foyer with a massive, embroidered chair that we believed to be a throne of some sort, always the smell of something wonderful cooking, the front bedroom with part of an ancient Cleveland Indians sticker on the mirror from when it was my uncles’ bedroom, the back bedroom filled with books, my grandmother’s bedroom redolent of perfume, her dresser covered with the jewelry, perfume and powder befitting a woman who had once been a model, and always been a beauty.

Outside, in warm weather, the sharp smell of Spirea, and a family with kids across the side street. It never occurred to me, as I played with them, that there was almost no furniture in their house, that the windows were broken, or that they were dirty and wore the same clothes all the time. I didn’t understand why my grandmother, head of the local Red Cross chapter, always insisted that they be fed something from the largesse in her refrigerator and pantry; sandwiches, homemade fudge, packets of leftover leg of lamb, noodle pudding and carrots. I didn’t understand until years after her death that the neighborhood was falling apart around her, that the death of the steel industry had left poverty, the end of Carlisle’s and the whole downtown, the conversion of surrounding houses into rentals, and an increasing threat to her safety. To me, the house lives on with its linoleum kitchen floor, the single bathroom with a claw-foot tub, the bathroom cabinets full of fascinating items like Sardoettes and Vitabath. It still smells of Ma Griffe, roasted meat, and the cool metallic smell of the back hall where can goods filled a series of compartments with individually latched doors. It is still my grandmother’s house, the house in which my mother grew up, and the house in which I felt completely adored, safe and cosseted in the way only a band of Hungarian Jews (or Greeks, or Italians, or Mexicans) can cosset a beloved little girl.

Outside, in warm weather, the sharp smell of Spirea, and a family with kids across the side street. It never occurred to me, as I played with them, that there was almost no furniture in their house, that the windows were broken, or that they were dirty and wore the same clothes all the time. I didn’t understand why my grandmother, head of the local Red Cross chapter, always insisted that they be fed something from the largesse in her refrigerator and pantry; sandwiches, homemade fudge, packets of leftover leg of lamb, noodle pudding and carrots. I didn’t understand until years after her death that the neighborhood was falling apart around her, that the death of the steel industry had left poverty, the end of Carlisle’s and the whole downtown, the conversion of surrounding houses into rentals, and an increasing threat to her safety. To me, the house lives on with its linoleum kitchen floor, the single bathroom with a claw-foot tub, the bathroom cabinets full of fascinating items like Sardoettes and Vitabath. It still smells of Ma Griffe, roasted meat, and the cool metallic smell of the back hall where can goods filled a series of compartments with individually latched doors. It is still my grandmother’s house, the house in which my mother grew up, and the house in which I felt completely adored, safe and cosseted in the way only a band of Hungarian Jews (or Greeks, or Italians, or Mexicans) can cosset a beloved little girl.

My other grandmother lived in North Providence Rhode Island, in a house that I loved maybe more than anyplace else I have ever been. It was on a corner, with an unused grape arbor in the back, and a stone wall overlooking the street on the side. Across the street lived the Feely family, large, Irish, loud, welcoming and (to me) magical. I played with Sean and Michael Feely every waking minute when I was in Rhode Island, and avoided playing with the drippy girl whose name escapes me, she of the Beautiful Chrissy doll, who used to stand outside my grandmother’s house calling plaintively for “Eee-ann” until my father asked her, gently, to knock it off.

Inside, there was Grammy Graham’s kitchen with the wall clock that played a German song, and a bread box with a box of Cheese Nips in it. I learned to make pie crust in that kitchen, rolling out my own scraps, sprinkling them with cinnamon and sugar, and patting them into my own tiny tins. We ate at a trestle table made by my grandfather (which is now my desk) sitting on long benches. It was very New England, from the row of peter tankards on the shelves of the hutch to the braided rugs on the floors made by Grammy over long winters.

Inside, there was Grammy Graham’s kitchen with the wall clock that played a German song, and a bread box with a box of Cheese Nips in it. I learned to make pie crust in that kitchen, rolling out my own scraps, sprinkling them with cinnamon and sugar, and patting them into my own tiny tins. We ate at a trestle table made by my grandfather (which is now my desk) sitting on long benches. It was very New England, from the row of peter tankards on the shelves of the hutch to the braided rugs on the floors made by Grammy over long winters.

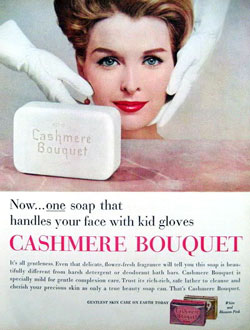

The bedspreads were white with little bobbly things on them, the bathroom smelled of a combination of Cashmere Bouquet soap and bandages, and the under part of the hutch had a pewter cream and sugar set in which I knew that there were always sugar cubes which I would remove using the tiny tongs, and dissolve on my tongue as I lay on the cool, hardwood floor. I slept, on summer visits, on a screened-in porch which was heaven to me. I was alone, close enough to hear my family moving about on the other side of the wall, cooled by the evening breezes, calmed by the swoosh of passing cars on the street below, feeling very grown up as I read into the night. Years later, long after my grandmother’s death, I persuaded a friend to drive me from Boston to Providence to see the house again. It had been changed; it was no longer the weathered blue-grey of my recollection, the arbor had been removed, and it was not Grammy’s house. I wept inconsolably, undoubtedly making my unsentimental friend wish he had made other plans.

The bedspreads were white with little bobbly things on them, the bathroom smelled of a combination of Cashmere Bouquet soap and bandages, and the under part of the hutch had a pewter cream and sugar set in which I knew that there were always sugar cubes which I would remove using the tiny tongs, and dissolve on my tongue as I lay on the cool, hardwood floor. I slept, on summer visits, on a screened-in porch which was heaven to me. I was alone, close enough to hear my family moving about on the other side of the wall, cooled by the evening breezes, calmed by the swoosh of passing cars on the street below, feeling very grown up as I read into the night. Years later, long after my grandmother’s death, I persuaded a friend to drive me from Boston to Providence to see the house again. It had been changed; it was no longer the weathered blue-grey of my recollection, the arbor had been removed, and it was not Grammy’s house. I wept inconsolably, undoubtedly making my unsentimental friend wish he had made other plans.

I still dream about both houses, disoriented until I am sufficiently conscious to understand that I am remembering only phantoms. The smells of roasting turkey and baking pie, the texture of nubby bedspreads, and the glimpse of an upstairs neighbor are lost to me except in my own mind. They spill out, no matter how vigilant my attempts to “be here now.” There is a Spirea bush near my own house, and there is a moment every spring when I catch its strong, sharp scent and I am twelve again, bumping up the red bricks of Chestnut Street, stretching after hours in the car and looking up to see my grandmother in the doorway at the top of the stairs. Mostly I live, in the present, but I am secretly pleased that I am so unenlightened that I can still travel back to the places that I preserve, in some dark and dusty memory book, like the loveliest of pressed flowers.

Ann Graham Nichols cooks and writes the Forest Street Kitchen blog in East Lansing, Michigan where she lives in a 1912 house with her husband, her son and an improbable number of animals.