I vividly remember my first exposure to the U.S. Presidential Election process. It was 1952, I was five years old, we had just bought our first television, and I was broken-hearted when an entire 30-minute episode of I Love Lucy was bumped so that Adlai E. Stevenson, the Democratic Party’s candidate, could present his platform to the American public. I wasn’t alone. Stevenson was barraged with hate mail from thousands of other disappointed fans. He had made history by being the first presidential candidate to use television as a way to promote his message, but he lost his bid for the presidency to Dwight D. Eisenhower who only interrupted the airwaves with a series of 20-second commercial spots.

I vividly remember my first exposure to the U.S. Presidential Election process. It was 1952, I was five years old, we had just bought our first television, and I was broken-hearted when an entire 30-minute episode of I Love Lucy was bumped so that Adlai E. Stevenson, the Democratic Party’s candidate, could present his platform to the American public. I wasn’t alone. Stevenson was barraged with hate mail from thousands of other disappointed fans. He had made history by being the first presidential candidate to use television as a way to promote his message, but he lost his bid for the presidency to Dwight D. Eisenhower who only interrupted the airwaves with a series of 20-second commercial spots.

Fast forward fifty-six years to one of the most historic elections our nation has yet witnessed. An African-American is leading the polls as the presidential candidate and the opposition is running a woman in the vice-presidential slot. In the nearly two years that this battle for the White House has been waged, thousands of television hours have been devoted to covering state-by-state caucuses, primary voting, stump speeches, and dozens of debates. Every network has its pundits who gleefully dissect every nuance and nod, and posit their predictions of what the eventual outcome might be. As the critical voting day draws near, battalions of volunteers canvass ‘swing’ districts in an effort to persuade the public to vote one way or another and ‘I have approved this message’ commercials pepper every program on every television channel.

Convincing the populace whom to vote for is half the battle. Getting voters to the polls is the next critical step. While our cousins Down Under solved the problem by simply slapping all non-voting Australians with a hefty fine, over the past two centuries American candidates have come up with some rather ingenious voter enticements. Working on the theory that an army marches on its stomach, our feuding factions have frequently mobilized their forces with food.

Feeding one’s faithful has a long and hallowed history. It figures prominently in both the Old and New testaments. When the Israelites were fleeing from their oppressors in the desert God rained manna on them “and the taste of it was like wafers made with honey.” Christ miraculously fed a multitude of 5,000 with five loaves of bread and two fishes, and when the liquid refreshments ran low at a friend’s wedding, he saved the day by changing water into wine. During the heyday of the Roman Empire, politicians maintained their power structure by distributing free bread and grain to the general population.

When Henry IV was crowned King of France in 1589, he said “I wish that every peasant may have a chicken in his pot on Sundays.” Several hundred years later, the phrase was resurrected. In 1928, America was riding the crest of a prosperity wave the likes of which had never been seen. Model T’s were rolling off Henry Ford’s assembly line, skirts were way up and prices were way down. The Republican Party, then in power, took all the credit for the nation’s financial boom. Their candidate, Herbert Hoover, ran for president on a platform that promised “A chicken in every pot and a car in every garage!”

When Henry IV was crowned King of France in 1589, he said “I wish that every peasant may have a chicken in his pot on Sundays.” Several hundred years later, the phrase was resurrected. In 1928, America was riding the crest of a prosperity wave the likes of which had never been seen. Model T’s were rolling off Henry Ford’s assembly line, skirts were way up and prices were way down. The Republican Party, then in power, took all the credit for the nation’s financial boom. Their candidate, Herbert Hoover, ran for president on a platform that promised “A chicken in every pot and a car in every garage!”

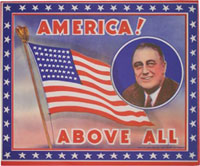

Unfortunately, like many a campaign pledge before and after, it went up in smoke. In the first year of Hoover’s administration, the stock market crashed bringing on the Great Depression. Charity run soup kitchens and bread lines sprang up all over. In 1932, the Democratic Party slogan was “Abolish Breadlines!” Their candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt swept the Presidential election. Four years later, high on the Repeal of Prohibition, their slogan was “Happy days are here again!” This time, Roosevelt’s landslide victory made history with a record-breaking voter turnout. Obviously, food and drink were subjects close to the American heart.

Unfortunately, like many a campaign pledge before and after, it went up in smoke. In the first year of Hoover’s administration, the stock market crashed bringing on the Great Depression. Charity run soup kitchens and bread lines sprang up all over. In 1932, the Democratic Party slogan was “Abolish Breadlines!” Their candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt swept the Presidential election. Four years later, high on the Repeal of Prohibition, their slogan was “Happy days are here again!” This time, Roosevelt’s landslide victory made history with a record-breaking voter turnout. Obviously, food and drink were subjects close to the American heart.

But comestibles have played a big part in our quadrennial Presidential election since the beginning. The first two times George Washington ran for a seat in Virginia’s House of Burgesses, he conducted a campaign against the saloons where the soldiers of his state’s armed forces tended to get too intoxicated to carry out their duties. He lost each election. On his third try, he provided gallons of hard cider and assorted other liquid refreshments for the voters and beat out three opponents. Later, Washington added suppers and entertainment to his election strategy.

In New England, one of the most important annual events was the election of officers to the county militias. Election Day, or Training Day as it was also known, gave the troops a chance to practice their parade drills, and provided the community with a carefree day of socializing around the town common. The festivities were accompanied by slices of Election Cake, gingerbread Training Cakes, and copious cups of mind-bending, vote-getting hard cider. Election cake was a raised yeast bread flavored with clove and cassia, the spice still used to flavor “red hot” candies. Baked in round loaves like bread, it was glazed with a sweet molasses-egg wash. Training Cakes, crisp cookie-like confections, were cut into geometric shapes and stamped with patriotic designs, the American Eagle being a favorite motif.

In New England, one of the most important annual events was the election of officers to the county militias. Election Day, or Training Day as it was also known, gave the troops a chance to practice their parade drills, and provided the community with a carefree day of socializing around the town common. The festivities were accompanied by slices of Election Cake, gingerbread Training Cakes, and copious cups of mind-bending, vote-getting hard cider. Election cake was a raised yeast bread flavored with clove and cassia, the spice still used to flavor “red hot” candies. Baked in round loaves like bread, it was glazed with a sweet molasses-egg wash. Training Cakes, crisp cookie-like confections, were cut into geometric shapes and stamped with patriotic designs, the American Eagle being a favorite motif.

In colonial times, public events were always accompanied by feasts. Invariably the host was a politically prominent gentleman. In keeping with his highly visible social position, he contributed an ox that was roasted on a huge bonfire, sliced and distributed to the townspeople on slabs of fresh baked bread. It was a good way to win friends and, at least temporarily, appease the disgruntled. After the Revolution, the outdoor roasting custom was transferred to political rallies.

At the rally held for Whig candidates Harrison and Tyler in Wilmington, Ohio in 1840, one thousand people gathered to build a log cabin and consume corn dodgers (baked cornmeal biscuits), barbecued ham, and every voter’s favorite thirst quencher: hard cider. The scene was repeated in upstate New York where a contemporary source reported “25,000 Freemen poured in from the valleys and rushed in torrents down from the mountains...vocal with eloquence and acclamations.” With the cabin and hard cider barrel portraying Harrison and Tyler as down-home frontier heroes, and friends of the farmer and the working-man, the motifs became the pictorial focus of the campaign. It is considered to be the first American national advertising blitz of any kind.

At these early presidential rallies, voters were often swayed more by what they ate and drank than by the candidates speeches and impassioned rhetoric. In the frontier states the rally highlight was a stew known as Kentucky Burgoo. The hearty concoction of beef, chicken, possum, squirrel and assorted vegetables took all day to prepare, and was served so frequently that supporters took to calling the rallies “Burgoos.”

Another wildly popular voting incentive was The Oyster Roast. Wagons loaded with oysters packed in seaweed were hauled overland, and served freshly shucked or steamed on hot coals to the hordes of voters who showed up to cast their ballots. And there was plenty of beer and hard cider to wash them down. In the latter half of the 19th century, voters in land-locked states were lured to the polls with oysters that had been shipped by train in barrels of ice, or boiled and sent on to be turned into savory oyster stews.

Another wildly popular voting incentive was The Oyster Roast. Wagons loaded with oysters packed in seaweed were hauled overland, and served freshly shucked or steamed on hot coals to the hordes of voters who showed up to cast their ballots. And there was plenty of beer and hard cider to wash them down. In the latter half of the 19th century, voters in land-locked states were lured to the polls with oysters that had been shipped by train in barrels of ice, or boiled and sent on to be turned into savory oyster stews.

By the mid-20th century, presidential conventions and campaign rallies had grown to be such enormous affairs that Party economics could no longer justify feeding their supporters on such exotic fare. Once upon a time all the eats and drinks were free, but today’s complimentary fare consists mainly of donuts and coffee for campaign workers and polling place volunteers. Rallies now take the form of fund-raising dinners where the price of admission can run upwards of $20,000 a plate. A notable exception occurs in the small community of Georgetown, Delaware.

Interestingly, this political food fest occurs not as a preamble to voting, but two days after the election. Known as Return Day, it began in 1791 when Georgetown was designated as the central voting location for Delaware’s Sussex County. Country folk came in horse drawn vehicles to cast their election ballots, and since news traveled slowly two centuries ago, they stayed over to hear the returns. The victorious candidate supplied a meal of pit-roasted ox and his loyal followers had a grand old time.

Interestingly, this political food fest occurs not as a preamble to voting, but two days after the election. Known as Return Day, it began in 1791 when Georgetown was designated as the central voting location for Delaware’s Sussex County. Country folk came in horse drawn vehicles to cast their election ballots, and since news traveled slowly two centuries ago, they stayed over to hear the returns. The victorious candidate supplied a meal of pit-roasted ox and his loyal followers had a grand old time.

With the advent of radio and television, election returns were announced almost immediately and it seemed the tradition would die off. Sussex residents chose to not only keep their celebration, complete with free roasted ox sandwiches for everyone attending, but added a new dimension to it. Since 1952, the high point of the celebration has been a parade in which leaders of both political parties ride together in a horse drawn carriage to the County Courthouse. There they symbolically bury a hatchet and pledge their intention of working together to the benefit of all. Bravo Georgetown citizens! You have initiated a custom all politicians would do well to follow.

Edythe Preet, former Culinary Historian for the Los Angeles Times Syndicate, presently heads up The Heritage Kitchen which offers a wide range of treats based on heirloom recipes as well as superb examples of mid-century American vintage linens.