There is a difference between jam and preserves. Jam is sweet fruit you spread on toast. Preserves are a frozen moment in time—a piece of summer that you can carry with you the rest of the year: high grass, long naps, warm evenings, your front porch…

There is a difference between jam and preserves. Jam is sweet fruit you spread on toast. Preserves are a frozen moment in time—a piece of summer that you can carry with you the rest of the year: high grass, long naps, warm evenings, your front porch…

My neighbor Mary Wellington makes preserves.

Mary is a farmer. And not only a single-family farmer--a single farmer. She works three acres of very diverse orchards of Glenn Annie canyon all by herself, on which she grows over fifty varieties of fruit. Her preserves were so treasured and ubiquitous at local farmer’s markets that many people came to call her “The Jam Lady.” Her Blenheim Apricot jam is intoxicating. Her Blood Orange marmalade is insane. The red raspberry is well… indescribable.

But Mary Wellington preserves more than fruit.

If you wander up Glen Annie you will find a two story clapboard farmhouse peeking out from behind the persimmon tree. Mary will greet you with her typical burst of enthusiasm and a clap of her hands. She will launch into an impromptu tour of her orchard and its latest bounty: You will flit from tree to tree sampling God’s offerings in a feast of the senses that is literally Edenic. (I know I get religious about food—but I was raised that way.) Taste the Santa Rosas… Smell the outside of this blood orange… Look at the color on these apricots... Oh don’t mind the bruise—just taste it.

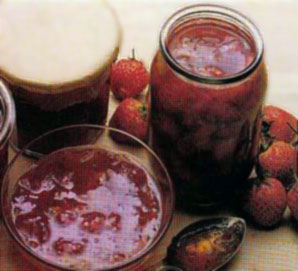

There are no herbicides to the keep the ground tidy. No pesticides either (the mixture of different varieties provides a habitat for beneficial insects that makes poisons unnecessary.) The fruit tastes amazing, and, as you stand there with the sun washing your face, tasting the flesh of a warm peach on a summer’s day, you do want the moment to last forever. And that’s what those mason jars are for.

Mary makes the best jam I’ve ever tasted. She doesn’t use any pectin—that’s for “busy” people who don’t care about preserving the taste of the fruit. Mary thickens her preserves the old fashioned way—in large pots with enough surface area to evaporate the water so you don’t need a thickening agent. It takes more time but it’s worth it. And as the afternoon wears on you begin to understand what the “slow food” movement is all about.

The act of preparation is everything. Meals (or jam) should be prepared with an awareness of the value of the food—a reverent act that actually connects you to the source of the meal and thereby your own survival. Someone actually picked that fruit. Someone caught that fish. Someone rolled that dough. When things don’t come from a package you develop an odd respect for their value, and when dinner is measured by the cost of your own labor you develop a keen connection to the field or tree or stream that gave it to you. Once it took all day make a meal. And when you take all day to make one, there is a wonderful upheaval in your sense of priorities.

Oddly enough all of this discourages gluttony. In a ravenous culture that is marked by its consumption, savoring a meal actually makes you slow down. You can eat ten Krispy Kreame doughnuts in a sitting, but you will linger over a piece of pie that took you hours to produce.

Santa Barbara is one of the few places in California where slowness is recognized as a virtue. The limits on growth, the snail’s pace of building permits, the myriad of bike lanes all tell you this is a micro-culture in which “speed” is not always seen as an end in itself. Mary Wellington made my whole family slow down to taste the fruits of her labor and we will be forever in her debt.

She taught my wife how to make jam her way… slowly… patiently… reverently... And my wife taught her friends. And they may teach their friends. And that is how you really “preserve” something.

Gary Ross is a writer director and occasional farmer who lives in LA, but grows stuff in the Goleta Valley, just North of Santa Barbara.