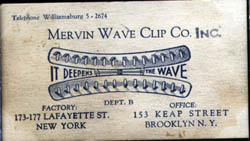

My grandfather Mervin was an inventor. He invented hairclips. To make money as a lad, he got a job sweeping up hair in a beauty parlor. Soon he noticed a need for clips. Clips that held the hair in place while the barber cut, clips that put waves in the hair, and doohickeys that crimped and flattened. He had patents on all these. Some were profitable, like the Jiffy, the Teeny, and others weren’t. But I guess the successful ones more than made up for the duds because he did pretty well for himself.

My grandfather Mervin was an inventor. He invented hairclips. To make money as a lad, he got a job sweeping up hair in a beauty parlor. Soon he noticed a need for clips. Clips that held the hair in place while the barber cut, clips that put waves in the hair, and doohickeys that crimped and flattened. He had patents on all these. Some were profitable, like the Jiffy, the Teeny, and others weren’t. But I guess the successful ones more than made up for the duds because he did pretty well for himself.

In the 1940s, his factory was at 173-177 Lafayette Street in Manhattan. Later he moved it to Orlando, Florida, though, when the workers tried to organize. In my family, we never liked unions much.

My grandfather Mervin was an inventor. He invented hairclips. To make money as a lad, he got a job sweeping up hair in a beauty parlor. Soon he noticed a need for clips. Clips that held the hair in place while the barber cut, clips that put waves in the hair, and doohickeys that crimped and flattened. He had patents on all these. Some were profitable, like the Jiffy, the Teeny, and others weren’t. But I guess the successful ones more than made up for the duds because he did pretty well for himself.

My grandfather Mervin was an inventor. He invented hairclips. To make money as a lad, he got a job sweeping up hair in a beauty parlor. Soon he noticed a need for clips. Clips that held the hair in place while the barber cut, clips that put waves in the hair, and doohickeys that crimped and flattened. He had patents on all these. Some were profitable, like the Jiffy, the Teeny, and others weren’t. But I guess the successful ones more than made up for the duds because he did pretty well for himself.

In the 1940s, his factory was at 173-177 Lafayette Street in Manhattan. Later he moved it to Orlando, Florida, though, when the workers tried to organize. In my family, we never liked unions much.

Fifty years later when I was living in SoHo, I wandered over to Chinatown to see what had happened to 173-177 Lafayette Street. I thought maybe the residue of the Mervin Wave Clip Company sign would be visible on the side of the building. The building was still there, but there was no sign of his sign. Everything was in Chinese. Mandarin or Cantonese, who knew?

Fifty years later when I was living in SoHo, I wandered over to Chinatown to see what had happened to 173-177 Lafayette Street. I thought maybe the residue of the Mervin Wave Clip Company sign would be visible on the side of the building. The building was still there, but there was no sign of his sign. Everything was in Chinese. Mandarin or Cantonese, who knew?

At the street level of the old factory was a discount store. I went in to poke around and tried to strike up a conversation with the man who worked there. The place was overflowing with merchandise dressed in colorful wrappers that made everything look like candy.

“My grandfather used to work in this building,” I said to the clerk who might have been the owner judging by the confidant pose he struck.

He nodded.

“This was back in the forties,” I said.

Again he nodded, and then smiled a little.

“Those were different times I guess,” I said.

“Time?” he managed. “Time is money.”

I bought a bag of candy and headed home. The candy turned out to be some kind of dehydrated noodle though.

After my grandfather moved the business to Orlando, he met a progressive doctor who only ate food grown in his garden: fruits, nuts, vegetables. Way, way, way ahead of his time, the doctor told my grandfather You are what you eat.

Over time, my grandfather heeded the man’s advice and became a vegetarian. As kids, my brother and I would visit him in Florida and he’d eat a tureen full of salad for dinner while we had chicken, steak, fish, the works. He never tried to get us to give up meat, but we wanted bigger salads than normal for dinner because his looked so good. There were sunflower seeds in there, chickpeas, flax seeds and something he had flown in especially from Washington state called dulse, which is a very salty, dry seaweed that he said was full of B vitamins.

Over time, my grandfather heeded the man’s advice and became a vegetarian. As kids, my brother and I would visit him in Florida and he’d eat a tureen full of salad for dinner while we had chicken, steak, fish, the works. He never tried to get us to give up meat, but we wanted bigger salads than normal for dinner because his looked so good. There were sunflower seeds in there, chickpeas, flax seeds and something he had flown in especially from Washington state called dulse, which is a very salty, dry seaweed that he said was full of B vitamins.

He also ate garlic cloves whole and liked to smear it on a piece of toast instead of butter or jam. When it came to apples, he ate the whole thing, including the core and the seeds. He’d say, “If a little seed like this has enough energy in it to produce an apple tree, can you imagine how good it is for you?”

I’d say, “Yeah, but they taste pretty lousy.”

He’d say, “So?”

There’s not much you can say to So. And anyway, it was pointless to argue with a man who peeled and bit into Bermuda onions the way the rest of us eat bananas.

My grandfather also loved mangos. He owned a tree on somebody’s property near I-95 and would drive over there to pick them when they were in season. But he couldn’t eat them fast enough, so every year he’d pack up liquor boxes with mangos wrapped in newspaper and ship them up to us in New Jersey. If we happened to be visiting him when they were in season, he’d send us home on the plane with a box, as well.

My grandfather also loved mangos. He owned a tree on somebody’s property near I-95 and would drive over there to pick them when they were in season. But he couldn’t eat them fast enough, so every year he’d pack up liquor boxes with mangos wrapped in newspaper and ship them up to us in New Jersey. If we happened to be visiting him when they were in season, he’d send us home on the plane with a box, as well.

The box was always taped close and wrapped with heavy rope he had found on the beach during his morning walks—something washed up from the sea. The rope made it easy to pick the box off the baggage carousel and kept the mangos safe inside.

But in his late 80s he couldn’t take those long walks on the beach anymore because a melanoma had metastasized to his liver. So the rope collection began to diminish. The last time I visited him in Florida, before he died, he was 91 and still insisted on packing a box of mangos for me to take back north.

I watched him carefully wrap each mango in newspaper and seal the box. Then he painstakingly looped the rope around the box and asked me to assist in making a square knot. When he was done, he looked at me with a sunken face and said, “Well, that’s the end of the rope.”

I watched him carefully wrap each mango in newspaper and seal the box. Then he painstakingly looped the rope around the box and asked me to assist in making a square knot. When he was done, he looked at me with a sunken face and said, “Well, that’s the end of the rope.”

And sadly, it really was. A month or so later, he was dead.

These days, I see people buying his wave clips off eBay and wonder what on earth they plan to do with them—if maybe the eBayers are just weird hairclip collectors or something. I also wonder who’s collecting all that rope on the beach now that my grandfather isn’t and wish I’d pay more attention when he was alive because I can’t seem to make a square knot without him.

David K. Israel is the author of the novel Behind Everyman. He's recently finished a second novel called The Art of Love (after Ovid) and writes a daily blog for www.mentalfloss.com.