A first serial excerpt from "Rubies in the Orchard," Lynda Resnick's autobiographical, how-to marketing gem. A road map for anyone who's trying to do anything in business or in life.

Running Teleflora was a dream job. I was in charge of marketing and product development, and, of course, I supervised all my new friends in the sales force, which I gradually shaped to fit my vision. The business was growing, and so were profits. I had reached a point where I could start delegating some of the work – provided I could let go of a certain nagging perfectionism (which today has a fancy name and a medication regime to go along with it).

My job was fulfilling, and my life with my husband Stewart and our kids had hit a stretch of smooth sailing, about as close to domestic bliss as any family gets. For the first time in my life, things seemed comfortable and easy. With everything going so well, there was naturally only one thing left to do: shake it up.

In 1981, I hired a news clipping service to begin tracking a direct-response company called the Franklin Mint. There were similarities between the Mint and Teleflora. The Mint created unique products, just as we did, only without the flowers. In those days, their products were mostly coins and medallions, a few porcelain vases, and some miniature knickknacks worthy of display in a “free with purchase” vitrine. Unlike Teleflora, the Mint sold its collectibles through direct response, with no middleman between the company and its consumers. It was something I longed to do.

The Franklin Mint was located in Philadelphia, where I was originally from. My best friend from childhood had grown up to be a hotshot recruiter, so I sent her into the Mint to find out who was creating their products. In no time at all, Stewart and I were sitting in our garden in California interviewing (or interrogating) the Mint’s V.P. of product development. He told me the company was poorly managed and grossly dysfunctional. And also said the Mint might be for sale. We hired that fellow to come to Teleflora, and I went on to persuade Stewart that the Mint might be our next acquisition.

Eventually, we paid a visit to the Mint’s campus. “You know, the collectibles business is dead. What do you think you are going to bring to the party?” one of the executives asked in his Philadelphia twang. In this person’s opinion, the current management was brilliant – and if they couldn’t make the business work, well, the likes of Stewart and I certainly weren’t going to get anywhere.

Eventually, we paid a visit to the Mint’s campus. “You know, the collectibles business is dead. What do you think you are going to bring to the party?” one of the executives asked in his Philadelphia twang. In this person’s opinion, the current management was brilliant – and if they couldn’t make the business work, well, the likes of Stewart and I certainly weren’t going to get anywhere.

The company was owned by Warner Bros. It had been one of the last acquisitions made by legendary Warner CEO Steve Ross, who loved it. He saw the same potential we did. Ross wasn’t eager to sell, but his video business, Atari, was hemorrhaging money and the Warner board was pushing for a sale. We were more than happy to relieve Warner Bros. of its perceived burden. This would be the end of my brief path of stress-free living.

Stewart and I lived in Beverly Hills, where we’ve been in the same house for thirty years. That meant quite a commute to the new office in Pennsylvania. We ended up living in a hotel in Philadelphia. Stewart said, “Don’t worry about this, we will turn the business around and be back in Beverly Hills in six months. You don’t even have to give up your job at Teleflora.” Right! For the first three months I almost believed him.

On our first day of work, I asked someone in the Mint’s Female Collectibles department about a doll on her shelf.

On our first day of work, I asked someone in the Mint’s Female Collectibles department about a doll on her shelf.

“Oh, that’s Scarlett O’Hara,” she sighed, “in her green dress from the barbecue.”

“Poor thing is covered all in dust. What happened?”

“Management doesn’t believe in Hollywood – it’s too riffraff. Conflicts with our image.”

Wow. I suddenly knew what I was bringing to the barbecue. Even through the dust, I could see that the doll was attractive, intriguing even, with fine features and an unmistakable aura of quality. Overnight, we were in the high-end collectible doll business. Our dolls were based on characters that were both real and fictional, but they all had a built-in following. Our first run of Scarlett generated $35 million in sales.

But our Gone With the Wind franchise didn’t begin and end with Scarlett. We produced dolls of Mammy, Rhett, Melanie, Prissy and just about every other character who had ever promenaded, strutted or crawled across the set of one of the great films of all time. Scarlett O’Hara wasn’t just a doll for us. She was an industry.

At the Mint, I learned how to predict and develop winning products. One of the first things I did was banish the word “customer” and replace it with “collector.” By referring to the people who bought our products as collectors, we immediately elevated them in the minds of our employees. And we let out collectors know that we understood their passion and respected it.

Our success depended on keen consumer insight. We conducted research and focus groups to understand our collectors’ deepest motivations and desires. Then we set out to meet their highest hopes. I’ve always believed in giving people more that they expect. It compliments not only their taste but their awareness and intelligence.

Our success depended on keen consumer insight. We conducted research and focus groups to understand our collectors’ deepest motivations and desires. Then we set out to meet their highest hopes. I’ve always believed in giving people more that they expect. It compliments not only their taste but their awareness and intelligence.

We staffed a research library that housed the artistic history of civilization. Through the efforts of our earnest librarians we could ensure that every detail of our products was authentic and true. I brought in decorative art scholars to educate the staff on everything from Gothic Revival and American Federal to French Rococo. When we copied a style, I wanted it to be accurate in every way.

Precision, craftsmanship, and careful attention to detail were essential – and we were able to charge a very healthy markup for delivering them. Because we cared about the intrinsic value of everything we produced, we attracted a loyal base of collectors who knew they got their money’s worth when they purchased from us. We understood that our products had emotional resonance. If you’ve always wanted a Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow but could never afford one, that die-cast model is a lot more than a shiny toy.

In order to keep the pipeline stocked with new products, I had a concept group whose sole task was to develop ideas: high-end dolls, collector plates, die-cast cars, male and female jewelry, bronzes, sculpture, porcelain figurines, coins, religious icons, doll houses, home décor and on and on. We tested anywhere from 1,000 to 1,500 new product ideas a year. We gauged how in tune we were with the market by the percentage of ideas that stuck.

To introduce our Marilyn Monroe doll collection (with Marilyn in the pink bow dress, of course), I needed a fine artist who could capture Marilyn’s unique mixture of innocence and raw sex appeal. I chose Emily Kaufman, but unfortunately, she demurred. Eventually, I convinced her that when she created a singular work of art, only one person could own it. But if she created a Marilyn sculpture for the Franklin Mint, thousands of people could own, enjoy, and treasure her work.

To introduce our Marilyn Monroe doll collection (with Marilyn in the pink bow dress, of course), I needed a fine artist who could capture Marilyn’s unique mixture of innocence and raw sex appeal. I chose Emily Kaufman, but unfortunately, she demurred. Eventually, I convinced her that when she created a singular work of art, only one person could own it. But if she created a Marilyn sculpture for the Franklin Mint, thousands of people could own, enjoy, and treasure her work.

Our licensing operation extended well beyond celebrities. In addition, we licensed Harley- Davidson along with practically every car company in the world, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Louvre, and even the Vatican – in the first ever deal of its kind. We located an original member of the Faberge family and licensed the name of the famous creators of Faberge eggs. We were able to reproduce priceless museum pieces that you didn’t have to be a tsar to collect.

All of our designs and illustrations were done in-house, as was the advertising, which emphasized both the history behind a product and the Mint’s fine attention to detail. In all our communications, we delivered the same message to collectors over and over again: We care.

If there is one venture that captured the essence of what was best about our business at the Mint, I think it would have to be the story of Jackie Kennedy’s pearls. Nothing I’ve ever done is more illustrative of the search for intrinsic value than that. Nothing better captures the effort to locate the rubies in the orchard than the case of Jackie’s pearls.

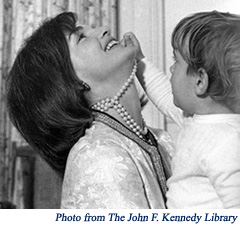

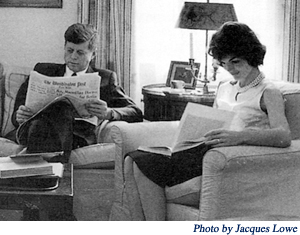

You know the pearls I’m talking about. Jacqueline Kennedy was so often photographed wearing those pearls they seemed a natural extension of her – and integral piece of her legendary grace and charm. She wore them to state dinners. She wore them on trips to India, Greece, and Japan. She wore them when she greeted the high and mighty and when she was looking after the children. Believe me – you know those pearls! But what you may not know is that the pearls were fake. Jacqueline Bouvier purchased them at Bergdorf Goodman in the 1950s for about $35.

You know the pearls I’m talking about. Jacqueline Kennedy was so often photographed wearing those pearls they seemed a natural extension of her – and integral piece of her legendary grace and charm. She wore them to state dinners. She wore them on trips to India, Greece, and Japan. She wore them when she greeted the high and mighty and when she was looking after the children. Believe me – you know those pearls! But what you may not know is that the pearls were fake. Jacqueline Bouvier purchased them at Bergdorf Goodman in the 1950s for about $35.

I worshipped Jackie Kennedy all my life. To me, she was the epitome of class; she managed to be beautiful, classy, and refined while still being refreshing, rather than stodgy or uptight. For millions of American women, Jackie was the standard by which every woman on the public stage was judged. She was the closest we would have to American royalty.

In 1996, Sotheby’s announced its “Auction of the Century” to sell the estate of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. I attacked the auction catalog like a rabid librarian who had just been released from the gulag. Yet despite my affection for the subject and my appreciation of her belongings, I could find only one thing in the entire auction that I wanted: those pearls. My staff was shocked by my restraint.

The catalog listed the estimate on the pearls at $200 to $300 dollars. Shrewd as I was, I suspected they might go a bit higher. In the weeks before the auction, I realized – time and time again – what a truly naive notion that was. As I kept pace with the constantly revised estimate, I did my best to keep Stewart up to date.

The catalog listed the estimate on the pearls at $200 to $300 dollars. Shrewd as I was, I suspected they might go a bit higher. In the weeks before the auction, I realized – time and time again – what a truly naive notion that was. As I kept pace with the constantly revised estimate, I did my best to keep Stewart up to date.

"Darling, I think we may have to go as high as five thousand dollars to get those pearls," I told him.

"They're fake, right?" he asked. "That's insane."

As the auction day neared, I gave Stewart the latest figure. “I think Jackie’s pearls may go as high as twenty-five thousand dollars,” I said.

“For a set of fake pearls? That’s just nuts.”

By this point, I had already talked myself into buying them. I wanted to convince Stewart that the investment – as crazy as it seemed – would be worthwhile. I spread photos across Stewart's desk – Jackie in the pearls here, Jackie in the pearls there, John-John on Jackie's lap pulling at those same pearls.

“She wore them in nearly every picture ever taken,” I said. “They are the icon of the icon.”

|

|

The day before the auction, the estimates were truly, undeniably insane – off the charts. I told Stewart the pearls might go for a ridiculous amount – maybe even $100,000. He just stared with incomprehension. The starting price was $5000. By the time the hammer came down on our winning bid, we had agreed to a final price of $211,000.00. We now owned the most expensive strand of fake pearls in the entire world.

We were not the only ones astonished by our willingness to pay such an absurd price. People magazine ran a story on the pearls, as did most U.S. newspapers. Dewar’s Scotch took out a full-page ad in The Wall Street Journal with the headline “Just pay $211,000 for a strand of fake pearls? You need a Dewar’s.”

We sent two guards from the Mint’s private army to New York to bring back the pearls. They delivered them to me directly at work. Everyone stood around and watched the unveiling. The pearls were still in their original silk-lined box from Bergdorf’s. As I opened it, I caught a faint scent of Jackie’s perfume. It was a chilling experience. My eyes welled up as I thought about what that divine creature had meant to me and my country.

We analyzed the 139 European glass faux pearls and made exact reproductions from a mold. The pearls were color-matched to the creamy originals, with the same seventeen coats of lacquer that the originals possessed. Then they were put on hand-knotted silken cords. The circle was closed by a silver art deco clasp featuring nine period-style rhinestones and bearing a Franklin Mint silver monogrammed emblem of authenticity. They were as close to the real fake Jackie pearls that any combination of art and technology could muster.

We analyzed the 139 European glass faux pearls and made exact reproductions from a mold. The pearls were color-matched to the creamy originals, with the same seventeen coats of lacquer that the originals possessed. Then they were put on hand-knotted silken cords. The circle was closed by a silver art deco clasp featuring nine period-style rhinestones and bearing a Franklin Mint silver monogrammed emblem of authenticity. They were as close to the real fake Jackie pearls that any combination of art and technology could muster.

We put the original strand of pearls on a coast-to-coast tour before bringing them home and exhibiting them at the Franklin Mint Museum. A couple of years ago, we made a gift of them to the nation; they are permanently on view at the Smithsonian.

At $211,000, the pearls turned out to be a phenomenal bargain. We sold more then 130,000 copies at $200 a strand – for a gross of $26 million. Owning the original pearls gave us the credibility to sell the copies; it certified and rewarded our collectors’ faith that they were getting as close to the real deal as anyone could. By wearing those iconic pearls, women everywhere could channel a bit of Jackie.

Rubies in the Orchard: How to Uncover the Hidden Gems in Your Business by Lynda Resnick with Francis Wilkinson. Copyright (c) 2009 Lynda Resnick. Published by Doubleday, a division of Random House. Available wherever books are sold. All Rights Reserved.