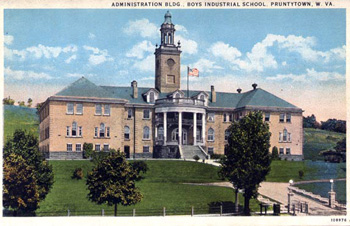

In November of 1980, I was the director of Juvenile Advocates, a legal advocacy program for incarcerated teens located in Morgantown, West Virginia. My job consisted of monitoring the treatment of juveniles who were locked up in county jails, detention centers and what were known then, as reform schools.Perhaps the most interesting part of the job was that about every two weeks I would drive the roller-coaster roads of the state to interview the kids locked up in the various institutions from the West Virginia Industrial School for Boys in

Pruntytown to the West Virginia Industrial School for Girls in Salem and the Leckie Youth Center, located way down in the coalfields of McDowell County.

In November of 1980, I was the director of Juvenile Advocates, a legal advocacy program for incarcerated teens located in Morgantown, West Virginia. My job consisted of monitoring the treatment of juveniles who were locked up in county jails, detention centers and what were known then, as reform schools.Perhaps the most interesting part of the job was that about every two weeks I would drive the roller-coaster roads of the state to interview the kids locked up in the various institutions from the West Virginia Industrial School for Boys in

Pruntytown to the West Virginia Industrial School for Girls in Salem and the Leckie Youth Center, located way down in the coalfields of McDowell County.

The names “Industrial School” and “Reform School” were vestiges of the early 20th century reform movement. Prior to that age of enlightenment, teenagers who broke the law were treated identical to adults. They were tried in criminal courts, locked up in state prisons along side adult inmates and even hung from the gallows. With the advent of the progressive movement, delinquency came to be thought of more as a social problem having its roots in poverty, discrimination and family disintegration.

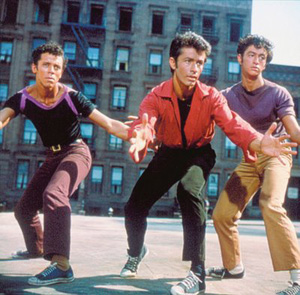

I could quote the great turn-of-the century social reformer Jane Adams, but I think the Jets provide the most eloquent explanation: “Dear Kindly Sgt. Krupke, you gotta understand, it’s just our upbringing upke that gets us out of hand, our mothers all are junkies, our fathers are all drunks, golly Moses naturally we’re punks.” Rather than punish

delinquents in prisons, the thinking went, they should be sent to schools to

be ‘reformed,’ made more ‘industrious.’

I could quote the great turn-of-the century social reformer Jane Adams, but I think the Jets provide the most eloquent explanation: “Dear Kindly Sgt. Krupke, you gotta understand, it’s just our upbringing upke that gets us out of hand, our mothers all are junkies, our fathers are all drunks, golly Moses naturally we’re punks.” Rather than punish

delinquents in prisons, the thinking went, they should be sent to schools to

be ‘reformed,’ made more ‘industrious.’

By the time I had arrived at the West Virginia Industrial School for Boys (originally named the West Virginia Reform School) – the facility I visited most frequently – in 1980, the lofty goal of rehabilitation had long ago given way to punishment, harsh punishment. The following from a West Virginia Supreme Court opinion is a description of some of these punitive practices, “‘Floor time’ was a punishment whereby the inmate apparently was required to stand stiffly in one position for several hours each day without talking… ‘Bench time’ was a punishment that required the inmate to sit in a specified location with arms crossed for several hours each day and for several days without talking or moving.” Other draconian measures, like making a boy hold a stack of books in out-stretched arms for hours at a time or forcing a boy down on his hands and knees to clean a floor with a tooth brush until the boy’s knees bled, were common.

The institution was based upon a behavioral modification treatment model where kids moved from level 1 through level 4 (the release level). But if you screwed up you were sent down to Level Zero. Each boy was assigned a different color shirt depending on his level and in the center of each shirt was the West Virginia seal along with the state motto, Montani Semper Liberi – Mountaineers are Always Free. Word.

Built in 1891, the administration building where I had a make-shift office, had the look and feel a massive stone fortress. The boys slept in dormitory cottages spread throughout the campus – unless of course they committed a serious infraction – like talking back to a CO or stealing food, then they would be sent to Level Zero and a tiny windowless cell.

I started my job in April 1980 and that November, I received an invitation to have Thanksgiving dinner at the Industrial School for Boys. Coincidentally, my mother was coming down from Long Island that same week to see me. She had not visited the state since I had moved there in 1978 and I wanted to show her the real West Virginia. What better way, than to invite her to Thanksgiving dinner at a reform school?

For most mothers, especially a Bronx-born Jewish mother, spending a holiday dinner at a juvenile prison would not necessarily be a prudent choice. But my mother was not just any Jewish mother. She was an old lefty who marched against the prosecution of the Rosenbergs,

escorted W.E.B. DuBois to political meetings and named me after Paul Robeson. I

figured Thanksgiving with 200 juvenile delinquents and their guards would be

perfect.

For most mothers, especially a Bronx-born Jewish mother, spending a holiday dinner at a juvenile prison would not necessarily be a prudent choice. But my mother was not just any Jewish mother. She was an old lefty who marched against the prosecution of the Rosenbergs,

escorted W.E.B. DuBois to political meetings and named me after Paul Robeson. I

figured Thanksgiving with 200 juvenile delinquents and their guards would be

perfect.

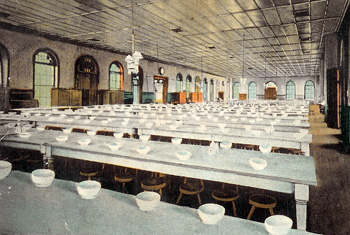

We arrived at the mess hall in the late afternoon and took our seats at a long table alongside the Warden, his wife, the assistant Warden and a priest. My mother of course sat next to the priest. All along the wall, guarding each exit was a stern-faced C.O. (corrections officer). The boys silently filed into the hall (that was a rule – they had to walk in single file and were not allowed to talk) and stood in front of their place setting: a yellow plastic plate, plastic water glass and plastic spoon and fork – no knives of course. Each boy stood in total silence until all of them were in the hall and when the word was given, they sat down at the same time – still in silence.

As she looked up and down the rows my mother whispered to me that they looked really skinny and sickly. She was expecting brawny, tough looking thugs but all she saw were scrawny pimply-faced kids with blank expressions. Before the boys sat down, we all rose and the priest gave the benediction. Even in reform school, you have to give thanks. As we sat down, the room was filled with a great flourish of plastic forks clapping against the hard plastic plates and huge whooshing slurps and lip smacks. Two hundred hungry teenage jaws chowing down creates its own unique din.

I called my mother the other day to ask what she recalled about that Thanksgiving meal. Two things jumped out – the mashed potatoes had a slightly green tinge to them even though they were made from powder and the cake had a bright pink frosting. All I remember is the

turkey swimming in a translucent brownish gravy and trying to cut it with the

side of a fork. My mother and the priest engaged in polite chit-chat, but

for the most part she looked shell-shocked. For her, the sea of lonely, young

faces was overwhelming. As soon as the pink cake was eaten, we left. It was

a Thanksgiving not to remember.

I called my mother the other day to ask what she recalled about that Thanksgiving meal. Two things jumped out – the mashed potatoes had a slightly green tinge to them even though they were made from powder and the cake had a bright pink frosting. All I remember is the

turkey swimming in a translucent brownish gravy and trying to cut it with the

side of a fork. My mother and the priest engaged in polite chit-chat, but

for the most part she looked shell-shocked. For her, the sea of lonely, young

faces was overwhelming. As soon as the pink cake was eaten, we left. It was

a Thanksgiving not to remember.

I was never invited back to another Thanksgiving dinner. I am pretty sure it had to do with the fact that over the next 3 years I was constantly filing lawsuits against the institution as well as every other reform school, forestry camp, detention center and jail in the state that violated a teenager’s rights. As a result of the these efforts and those of other juvenile rights attorneys, the West Virginia Industrial School for Boys eventually was closed down in 1983.

Paul Mones is nationally recognized children's rights attorney specializing in representing sexual abuse victims and teens who kill their parents. He is also a published author and most importantly an avid chef who won the 1978 North Carolina Pork Barbecue Championship.