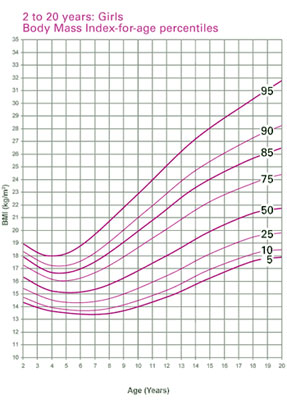

“Do you see this chart, Lynne? This is your height-weight percentile chart. And do you see where you are? You’re waaaaaay up here. Waaay past the 90th percentile. Do you see that? How would you like a shot to suck all the fat away?”

“Do you see this chart, Lynne? This is your height-weight percentile chart. And do you see where you are? You’re waaaaaay up here. Waaay past the 90th percentile. Do you see that? How would you like a shot to suck all the fat away?”

Ok. So Dr. Salvo didn’t sound quite that evil, but it’s not too far off. To this day, whenever I hear the word “percentile,” no matter the context, I cringe a little, remembering the good doctor showing me my elevated, childhood status on the red-lined chart. And why did it have to be red? As if being a chubby little kid were cause for dire emergency.

He really did ask me if I wanted a shot that would “suck all the fat away.” At the time I remember shuddering and saying no, needle-phobic as most little kids are. Then, down the road a little bit, in my pubescence, I remember regretting telling him I didn’t want the shot. What if he really did have one? What if I could have saved myself all this pain? All this praying at night that I’d wake up thin?

Cut to 30 years old, about 50 pounds less than my early-college weight-peak, and several thousand dollars into 5 years of therapy, and I can finally see Dr. Salvo for what he was: an asshole. But though I have gained a great deal more comfort with my body, I still find I have a complicated relationship to weight. I think it’s hard not to in this culture.

In 2008 I got Mono. Thank you, no, I was not making out with 18 year olds. The sickness dropped me down to the lowest weight I’ve ever been (and likely will ever be again), and people regularly applauded me for it. Even after I’d tell them why, they’d reply with some version of “still, you look great.” And even though the logical thinker in me knew this spoke to a serious problem in our collective mindset, the weight-obsessed kid in me was thrilled – until I got better and started eating again.

A week ago I attended a meditation event and, overcome with sleepiness, I opened my eyes to take in some visual stimulus. They landed on a thin young woman in a sundress, perched on a cushion a few feet in front of me. Almost unconsciously the thought popped into my head, “She has a body that no one disagrees with.”

I have a body some people disagree with. I’m 5’2” of curves, flesh and muscle. Hollywood, for instance, disagrees with my body, for any role other than “best friend” or, in a few years, “mom.” The fashion industry disagrees with my body. A certain population of rail-loving men disagree with it. Even my primary care physician seems to disagree with it, pointing out a number on a scale, rather than the fact that I am a certified yoga teacher, who can happily bike 10-20 miles in 90 degree heat.

I have a body some people disagree with. I’m 5’2” of curves, flesh and muscle. Hollywood, for instance, disagrees with my body, for any role other than “best friend” or, in a few years, “mom.” The fashion industry disagrees with my body. A certain population of rail-loving men disagree with it. Even my primary care physician seems to disagree with it, pointing out a number on a scale, rather than the fact that I am a certified yoga teacher, who can happily bike 10-20 miles in 90 degree heat.

Of course, I projected all over the poor girl. She could potentially have all sorts of self-esteem issues. But I wondered, looking at this small woman, what it would be like to have a body the collective culture wouldn’t question? And then, further, what it would be like to not have an agreeing or disagreeing society in the first place? What would it be like not to care? To never have been conditioned to notice her weight?

It’s not that I don’t recognize there are obesity problems in the United States. But there is a distinct difference between genuine medical concern for obesity, and the flesh-phobic society into which we have evolved. If, in the media and in our personal lives, we could all stop talking about one another’s weight – gain, lose or otherwise – what other aspects of self-flagellation could we address? If people in my life would stop telling me my new “thinner” is “better,” how much more space could I find between my present self, and the Dr. Salvo that lingers in my head?