Once upon a time in a kitchen far, far away, I was often babysat by my grandma in our fairy tale of a family deli in downtown New Haven, Ct. I could have done worse. She, a sorceress of superb taste, made ruggelach fresh daily, with me assisting, eating fistfuls of walnuts that 'just happened' to fall from the dough, licking the battered bowl of elixir from the cake

preparations, eating crumbs that magically broke off the babka. My mouth was as busy as my hands as I ingested the mysteries of grandma’s cuisine.

Once upon a time in a kitchen far, far away, I was often babysat by my grandma in our fairy tale of a family deli in downtown New Haven, Ct. I could have done worse. She, a sorceress of superb taste, made ruggelach fresh daily, with me assisting, eating fistfuls of walnuts that 'just happened' to fall from the dough, licking the battered bowl of elixir from the cake

preparations, eating crumbs that magically broke off the babka. My mouth was as busy as my hands as I ingested the mysteries of grandma’s cuisine.

We were major meat eaters in those innocent days, breakfast, lunch, noshes, suppers and snacks. How could we not be, with kosher creatures sticking out their tongues or lolling seductively about in grandpa's display cases? Lunches of exotic fare like liverwurst, baloney, pastrami, corned beef and melt-in-your-mouth scoops of the Chartoff chopped liver filled my plate. Pieces of the ubiquitous Hebrew National salamis were served in challah sandwiches, on toothpicks, fried up with eggs or put on my grandpa's homemade pizzas. Grandma's brisket was to die for, and she and grandpa left the earth from heart disease far too soon to prove it.

Once upon a time in a kitchen far, far away, I was often babysat by my grandma in our fairy tale of a family deli in downtown New Haven, Ct. I could have done worse. She, a sorceress of superb taste, made ruggelach fresh daily, with me assisting, eating fistfuls of walnuts that 'just happened' to fall from the dough, licking the battered bowl of elixir from the cake

preparations, eating crumbs that magically broke off the babka. My mouth was as busy as my hands as I ingested the mysteries of grandma’s cuisine.

Once upon a time in a kitchen far, far away, I was often babysat by my grandma in our fairy tale of a family deli in downtown New Haven, Ct. I could have done worse. She, a sorceress of superb taste, made ruggelach fresh daily, with me assisting, eating fistfuls of walnuts that 'just happened' to fall from the dough, licking the battered bowl of elixir from the cake

preparations, eating crumbs that magically broke off the babka. My mouth was as busy as my hands as I ingested the mysteries of grandma’s cuisine.

We were major meat eaters in those innocent days, breakfast, lunch, noshes, suppers and snacks. How could we not be, with kosher creatures sticking out their tongues or lolling seductively about in grandpa's display cases? Lunches of exotic fare like liverwurst, baloney, pastrami, corned beef and melt-in-your-mouth scoops of the Chartoff chopped liver filled my plate. Pieces of the ubiquitous Hebrew National salamis were served in challah sandwiches, on toothpicks, fried up with eggs or put on my grandpa's homemade pizzas. Grandma's brisket was to die for, and she and grandpa left the earth from heart disease far too soon to prove it.

Hence, the alchemy of vegetarianism became my path when I moved into independence in Manhattan, making food choices from educated fears rather than the addictive flavors of family bonding. But, I was allergic to soy, and on the outs with sprouts while I fantasized about the fine, fatty foods of my childhood more than such blah, bland, lean steamed greens of my enlightened youth. The healthy veggie life seemed way too staid to my cursed, smell-shocked tastebuds.

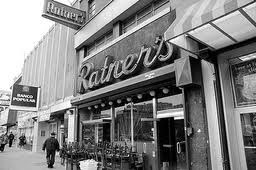

Fortunately, I found Ratner's 2nd Avenue Restaurant while rehearsing for my first Broadway show, "Via Galactica" with Raoul Julia at the Ukrainian Home across the street. He knew how homesick I was for the hamisha foods of my youth amidst the scary big world of commercial NY Theater. We took our lunch hours far away thematically from our high tech, space age, rock opera rehearsals, in an ancient world of afficionados ingesting gorgeous beet borschts, filling

cheese blintzes, crunchy garlic bagels and nurturing barley soup at the

restaurant. Hearing Puerto Rican Raoul order ‘kugel’ and “kasha”

cracked me up.

Fortunately, I found Ratner's 2nd Avenue Restaurant while rehearsing for my first Broadway show, "Via Galactica" with Raoul Julia at the Ukrainian Home across the street. He knew how homesick I was for the hamisha foods of my youth amidst the scary big world of commercial NY Theater. We took our lunch hours far away thematically from our high tech, space age, rock opera rehearsals, in an ancient world of afficionados ingesting gorgeous beet borschts, filling

cheese blintzes, crunchy garlic bagels and nurturing barley soup at the

restaurant. Hearing Puerto Rican Raoul order ‘kugel’ and “kasha”

cracked me up.

And we weren’t the only performers eating there. Such noshing notables as Abbe Lane, Jackie Mason, Elia Kazan, Edie Gorme, Zero Mostel, Henny Youngman, and a few Rockefellers were often breaking onion bread nearby. The Fillmore East had just closed next door, but the roadies and their legends of Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison slurping Ratner’s matzoh ball soup lived on.

Far from elegant, with no VIP tables, and equal opportunity offensive waitresses, the Ratner’s atmosphere and staff made all feel at home – teased and overfed. It was astonishing to me that Jewish food had become the traditional show biz food. And away from home, out of college cafeterias, with a small kitchen of my own in Greenwich Village, I longed to make my home smell like Grandma’s, yet keep my heart safe like Ratner’s.

Then, I learned of Ratner's Meatless Cookbook. The magical meals of my past became demystified at last. Exotic tastes became traceable ingredients. Because I was reared on yellowed, handwritten, hand me down recipes, stained with Crisco, crumbed with cinnamon, and because my father always shooed us all out of the kitchen as he recreated the deli dishes, I had never even read a cookbook til Elizabeth Lefft and Judy Gethers' great

assemblage of the greatest hits of the original Ratner's Dairy Restaurant on

Delancey St. gave me reason to feast. Here were the foods of my family, reframed sans

cruelty to animals or heart valves, yet captivating in texture and

taste.

Then, I learned of Ratner's Meatless Cookbook. The magical meals of my past became demystified at last. Exotic tastes became traceable ingredients. Because I was reared on yellowed, handwritten, hand me down recipes, stained with Crisco, crumbed with cinnamon, and because my father always shooed us all out of the kitchen as he recreated the deli dishes, I had never even read a cookbook til Elizabeth Lefft and Judy Gethers' great

assemblage of the greatest hits of the original Ratner's Dairy Restaurant on

Delancey St. gave me reason to feast. Here were the foods of my family, reframed sans

cruelty to animals or heart valves, yet captivating in texture and

taste.

To this day, I can trip back to the past concocting one of their great dishes and recall some of my dearest days dining in my bubbe’s deli kitchen, and in the nostalgic last days of Ratner’s itself.

From Ratner’s Meatless Cookbook, here is Ratner’s mock chopped liver, a trompe le tongue in which lean lentils masquerade convincingly as meat.

RATNER'S MOCK CHOPPED LIVER

½ pound cooked lentils

2 cups chopped onion

8 hard-cooked eggs

3 tablespoons oil

1 tablespoon peanut butter

¼ teaspoon white pepper

1 teaspoon salt

Lettuce

Horseradish

Tomato slices

Drain the precooked lentils. Pour ½ Cup Onion into a bowl. Chop the eggs finely. Add eggs and lentils to the bowl. Sauté remaining onions in half the oil until brown. Mix lentil mixture with sautéed onions, the remaining oil, peanut butter, pepper and salt.

Serve on lettuce leaves with white or red horseradish and a slice of tomato.

Previously printed in Jewlarious, Oct. 2010.