There’s nothing like Halloween in New York City. New York is home to some of the most artistic and creative people on the planet, most of whom will jump at any opportunity to put on a show. Consider the city’s eight hundred thousand drag queens, who, just to take a trip out to the deli, will put on seven-inch platforms, a sequined butterfly shawl and a two-foot wig. In the weeks before Halloween, the whole city began to fill with a fizzy, randy excitement. Shop windows were crammed with bondage gear, feather boas, broquaded undies and outrageous wigs, and the window boxes of the West Village overflowed with chrysanthemums and pumpkins and squash—all in their final bursts of color before the decay of the winter set in. And all those flamboyant colors; all those sequins, feathers and rubber masks started to bring out everyone’s inner drag queen. And it was no different for the dog people. There are more that thirty dog runs in the city, and therefore more than thirty annual doggie costume parades.

There’s nothing like Halloween in New York City. New York is home to some of the most artistic and creative people on the planet, most of whom will jump at any opportunity to put on a show. Consider the city’s eight hundred thousand drag queens, who, just to take a trip out to the deli, will put on seven-inch platforms, a sequined butterfly shawl and a two-foot wig. In the weeks before Halloween, the whole city began to fill with a fizzy, randy excitement. Shop windows were crammed with bondage gear, feather boas, broquaded undies and outrageous wigs, and the window boxes of the West Village overflowed with chrysanthemums and pumpkins and squash—all in their final bursts of color before the decay of the winter set in. And all those flamboyant colors; all those sequins, feathers and rubber masks started to bring out everyone’s inner drag queen. And it was no different for the dog people. There are more that thirty dog runs in the city, and therefore more than thirty annual doggie costume parades.

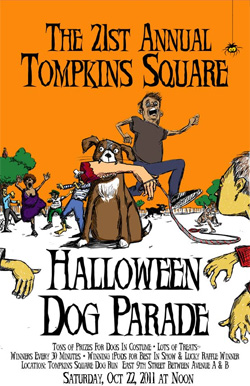

At that point in time (1998) we had just started taking Wallace to the Tompkins Square Park dog run. Each run in the city has its own flavor and “First Run” as it was called (because it was the first in NYC) was known for 1) the youth of its doggie parents (most were East Village kids in their twenties); 2) the number of pit-bull mixes (most of the young doggie parents adopted pits from the ASCPA in the East 90’s, or found them on the streets); 3) the number of dog-brawls that occurred daily (it was a transient neighborhood, with a lot of new dogs); and 4) The legendary First Run Annual Halloween Costume Contest, which drew the likes of Iggy Pop and Lou Reed.

When I first saw the sign for this Halloween contest in early October, I felt my entire universe expand. Dogs in costume! At the thought of this, something latent was awakened in me—something ancient and profound. I told my then-husband Ted in no uncertain terms that we had to go to this contest.

“Are you thinking of dressing Wallace in a costume?” Ted asked.

“Absolutely.”

“He’ll hate it.”

“No he won’t.”

Most conversations I had with Ted went like this: yes, no, yes, no, why, because, no, yes, I said no, yes, no, FUCK YOU!

In the case of whether to dress up our dog in a silly costume, I ultimately won. I can’t remember how, actually. Perhaps I had to promise some sort of sexual favor, but it’s hard to say....I’ve blocked it all out.

Anyway, I managed to convince Ted that Wallace wouldn’t mind having to wear a costume. I can’t remember how we came up with the idea, but we had decided to dress him up like a little hiker. I think it all started with this brown wool hippy hat that used to belong to a stoner friend of Ted’s from high school. The hat was handmade in Peru, and slightly pointy on top, and had two strings that you could tie under your chin. Ted had asked me once if I wanted it, but I am much too serious a person to wear silly Peruvian hats. (The hats I wear cost $550 and I never even wear those, because I always buy them on a whim, and they are really only appropriate at English garden weddings, and I have not yet to date been invited to any weddings in the UK.) So anyway, I suggested we put the Peruvian hat on Wallace, just for kicks.

Anyway, I managed to convince Ted that Wallace wouldn’t mind having to wear a costume. I can’t remember how we came up with the idea, but we had decided to dress him up like a little hiker. I think it all started with this brown wool hippy hat that used to belong to a stoner friend of Ted’s from high school. The hat was handmade in Peru, and slightly pointy on top, and had two strings that you could tie under your chin. Ted had asked me once if I wanted it, but I am much too serious a person to wear silly Peruvian hats. (The hats I wear cost $550 and I never even wear those, because I always buy them on a whim, and they are really only appropriate at English garden weddings, and I have not yet to date been invited to any weddings in the UK.) So anyway, I suggested we put the Peruvian hat on Wallace, just for kicks.

This opened up a can of worms, of course, that determined much of Wallace’s future. For I quickly realized that I got a true and unadulterated pleasure from dressing up my dog.

“He looks so cute,” I shouted. “Oh my God. Get the camera.”

“The poor boy,” Ted said. “How humiliating.” But still Ted got the camera.

The rest of Wallace’s Halloween costume quickly fell into place. Wallace already had his own little backpack, for camping trips, and Ted agreed to donate a pair of ratty hiking shorts he’d had for years. He started to have regrets, however, when I spent $30 on a little wool sweater and cut strategic holes in his cherished shorts to accommodate Wallace’s tail and privates, but by then it was too late. The contest was only one day away.

“You’re going overboard,” he said the next morning as I gussied up Wallace. “Everyone else will probably show up with their dogs in cat ears and witch hats.”

“So what?” I said. “This is fun. Plus, we’ll win.” For a final touch, I put a Catskills trail guide in the pocket of Wallace’s backpack, so that there would be no doubt that he was a hiker.

The day itself was one of those perfect fall days you read about: crisp, cool, clear, with the scent of autumn leaves and hot cider donuts lingering in the air. I insisted on dressing up Wallace at the apartment and couldn’t contain my excitement at the cuteness of it all. I started to have visions of Wallace being in the movies, of starring in dog food commercials, of his face gracing millions of cutesy-dog greeting cards. And a photographer from the Times would definitely be at the contest—one came every year. So maybe finally I’d get my picture in that paper. With my award-winning dog.

“Oh my god, he’s so cute!” I said for the millionth time. (If I couldn’t have my own time in the spotlight, then, by God, Wallace was going to have his.) “Will you take a picture of him before we leave? It’s his first party, in his first party suit.”

“Let’s not prolong the torture,” Ted said. “The poor boy.” Admittedly, Wallace did look downtrodden, as if he wished he had nothing to do with the human world. He kept lifting his eyelids, and twisting his head left to right, trying to figure out what was on top of his head. He also tried to pull off the backpack with his mouth, but he couldn’t quite reach.

“Let’s just go!” Ted said.

I enjoyed all the attention we got on our twenty-minute walk to the dog run. “Look at that dog!” people on the sidewalks shouted. “He’s so cute!” All around us, people laughed and pointed and smiled. I basked in their praise; I loved being in the spotlight, even indirectly.

But Ted seemed pained. “He’s such a dignified dog,” he kept saying as we walked through the East Village. “This isn’t right. You’re humiliating him. He’s going to grow up to be a pansy. He’s going to be like Hemingway, who was all screwed up because his grandmother dressed him in girlie clothes.”

“No, he’s not,” I said, undaunted. I stopped to talk to strangers and told everyone cute little anecdotes about Wallace. “He used to be a shelter dog,” I would begin. “And he used to hate us. And he would never let us touch his head. And now look at him with his little hat….”

“Wallace come,” Ted would say, pulling on the leash.

“Wallace was enjoying himself,” I said to Ted when I caught up to him.

“That’s because that woman petting him has a hot dog.”

“No it’s not. It’s because she told him he was cute.”

On and on this went, all the way to the park. It wasn’t until a horde of pretty girls in go-go boots ran up to Ted to ask what kind of dog Wallace was, that the tight, slightly pained look left Ted’s face.

On and on this went, all the way to the park. It wasn’t until a horde of pretty girls in go-go boots ran up to Ted to ask what kind of dog Wallace was, that the tight, slightly pained look left Ted’s face.

When we reached the grassy area within Tompkins Square Park, Wallace went immediately went into hunting mode. His steps slowed, his torso sank lower to the ground, and his nose twitched with the precision of a sonograph as he picked up subtle scents. You could tell he had forgotten he had a little ski cap on, and a backpack, and a toddler’s sweater and silly shorts. “Look at him stalking those squirrels!” the girls in the go-go boots shouted.

“Poor Wallace,” Ted muttered. “The poor emasculated boy.” But this hadn’t stopped him from bringing along his video camera. He followed Wallace along, zooming in for close-ups, as Wallace crept slowly toward a squirrel.

When we finally reached the dog run, I was astounded at what I saw. You’re always going to find, at every Halloween contest across the country, a lab in Christmas antlers, and one or two Dog-zillas, and a golden retriever in a store-bought Yankees cap. But try to picture a Harlequin Great Dane dressed up as a giant sunflower. Or a matted grey Shitzhu dressed as a mop and accompanied by a short gay man dressed as a frumpy housewife. The costumes were spectacular. There was a shepherd mix in a curly black wig and Gene Simmons makeup, and a tiny leather jacket embossed with the logo: Kiss.

There was a couple dressed up like farmers, carrying baskets of produce, and tucked within the vegetables was a tiny Chihuahua in a pea pod costume, shivering nervously the way Chihuahuas do. There were Pit Bulls sporting cow udders, and six Dachshunds spray-painted yellow to look like a bunch of bananas, accompanied by a giant man in a gorilla suit.

There was a couple dressed up like farmers, carrying baskets of produce, and tucked within the vegetables was a tiny Chihuahua in a pea pod costume, shivering nervously the way Chihuahuas do. There were Pit Bulls sporting cow udders, and six Dachshunds spray-painted yellow to look like a bunch of bananas, accompanied by a giant man in a gorilla suit.

“Wow,” Ted said. “I’m impressed.”

“I’m depressed,” I said. One of the great, but also one of the rotten, things about New York City is that no matter how creative you are, no matter how talented or clever or smart, there’s always going to be someone out there who’s smarter and more talented and more creative than you. Every second of every day.

“Look at that costume!” Ted said. And there I beheld my nemesis. Across the run, wearing Gucci sunglasses and surrounded by adoring fans, was a man and his golden retriever, whom he had fashioned into a Three Headed Dog. From a distance the two extra heads looked life-like, and they continued to look life like even as we got close. “How did you do that?” someone asked, through a crowd that was three-people deep. “With Styrofoam,” he explained. “I’m a set designer.” And he went on to describe how he had begun constructing the heads back in August, how he had required his dog, Butterscotch, to pose for an hour each evening as he painted her likeness on the busts, and how it had taken him three weeks to find the best “suspension mechanisms” to attach the heads to Butterscotch’s collar. Then of course he had to go out and find the perfect cape to conceal the suspension mechanisms. And the cape had come from Shanghai Tang (a high-end Asian boutique on Madison Avenue).

“That shawl had to have cost six hundred dollars,” I said to Ted as we slunk away. “And did you see that they eyes on the Styrofoam heads actually blinked?”

“I’m blown away,” Ted said.

“If I had known people were going to spend six months on their costumes, I would have put more effort into Wallace’s.” I stared at the three-headed dog’s magnificent cape. “I don’t even have socks from Shanghai Tang.”

“But look our puppy, he’s adorable,” Ted said. “And he’s being such a good boy.” Wallace always stayed by our side at the dog run, because he was still intimidated by the presence of so many dogs. “Come on,” Ted said. “Let’s go sign him in.”

When we got to the registration desk, we found out we had to have a name for Wallace’s costume. I hadn’t thought of a name. I thought the costume spoke for itself. To me, Wallace looked like a little hippie kid, a Bates student, a Trustafarian going off on a hike. “How about Happy Camper?” I said to Ted.

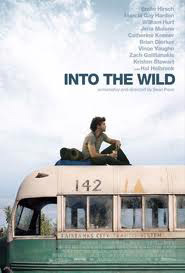

And don’t they always say First Thought, Best Thought? Because then, for some reason, I decided that I had needed to have a more literary name. Something more clever and tongue-in-cheek. I thought then of Jon Krakauer, the author of Into The Wild.

“No one is going to know what you’re talking about,” Ted said.

“No one is going to know what you’re talking about,” Ted said.

But I reasoned that we were in the East Village, a neighborhood full of artists and writers and tortured souls. Any of the above would certainly have read Into the Wild, which was the “it” book of the moment. So we—or rather, I—registered Wallace as “Jon Krakauer” and we took our place in line for the parade to begin. Ted gave me one of his looks—one I liked to call “The Crow.”

The contest began by everyone parading their dogs around the perimeter of the run as a group, and then each of the contestants was called one by one. The whole dog run was lined with was lined with giddy onlookers. As each contestant was called forth they hooted and clapped and cheered. The sound of so much applause was uplifting, and I laughing along, but then Wallace’s name was called. The MC said: “And here’s Wallace the English Setter, and he’s posing as, as, um, Jonathan Kra……Jon Cracker?” The crowd, who had just been cheering madly for the Mastiff-as-ballerina before us, now grew silent.

In this void, I told Wallace to heel and we promenaded along. I smiled nervously and fakely, like a beauty contestant finalist who has just found out she was eliminated after just the first round. I tried to make eye contact with Ted, who was out there somewhere with the onlookers, but I couldn’t find him in such a crowd. Then our moment was over. Wallace and I returned to our place in line, and then some other dog’s name was called. “That was our fifteen minutes of fame,” I whispered to the dog. “And it sucked!”

The Three-Headed Dog won of course, soon the dog and his costume designer were mobbed by photographers and fans. Dejectedly, I took off Wallace’s short and backpack, so that he could go and happily hump the ballerina and bite other dog’s necks. “I should have just called him the Happy Camper,” I said to Ted as I stuffed Wallace’s little hiking shorts into my bag. Across the run, I watched people congratulate the set designer. He seemed a bit too proud of his achievements; a bit too smug.

Ted thought the whole thing was hilarious. “Jon Krakauer,” he said over and over again. “Into the Wild!” He trained his video camera onto me and said, “This is Lee pouting because Wallace didn’t win the Halloween contest.”

When he saw that I wasn’t laughing, he said. “Let’s go to Veselka’s and get some lunch.” Ted, like all good city boyfriends, knew that certain restaurants could always cheer certain mopey women up. For me, it was Veselka’s: pirogues (steamed, and stuffed with potatoes, cheese and broccoli), French fries, and a cold Pilsner Urquell on tap.

When he saw that I wasn’t laughing, he said. “Let’s go to Veselka’s and get some lunch.” Ted, like all good city boyfriends, knew that certain restaurants could always cheer certain mopey women up. For me, it was Veselka’s: pirogues (steamed, and stuffed with potatoes, cheese and broccoli), French fries, and a cold Pilsner Urquell on tap.

We leashed up Wallace and headed off. As we were leaving the park, a nice young woman ran up and touched my shoulder. “I thought yours was the best costume.”

“Really?” I turned to her and smiled.

“He should have won first place.”

“Thanks.”

This is one of the wonderful things about New York: for every stranger who has the capacity to ruin your day—whether deliberately or not—there are always two or three more strangers who will extend to you a fresh, pure act of kindness.

“See?” I said to Ted at Veselka’s. “Someone got it. I wasn’t totally out of line.”

“Yes, Lee,” he said. “One in twelve hundred people gets you.” He touched my hand. “Make that two.” Wallace, as if he understood us, turned around at that moment and looked at us with what we call his “treat face.”

“Make that three,” Ted said.

This is not where the story ends, however, because from that day forward, for the next two years I tried to devise schemes to out-do the Three Headed Dog and his set designer man.

It was now the year 2000 and, much to my disappointment, the world had not ended as everyone kept insisting it would. Thus, I had to continue living my drudgery of a life. I started thinking about Wallace’s costume in early August. Ted and I would be walking along the beach at Fire Island, or hiking in the Hudson Valley, swatting away flies, and I’d say things like, “What do you think of Tommy Hilsetter?”

“What?” Ted would say. “What are you talking about?” He was a serious hiker, who always kept his eyes on the trails, and therefore never really listened to me while he was hiking. Perhaps—and I am seriously just realizing this now, as I write: perhaps this is why he liked hiking so much. It was the only time he could legitimately tune me out.

“For Halloween,” I said. “We could put a little skull cap on him, and really baggy jeans that hang low off his butt. He could be a little ghetto dog.”

“I think that might be offensive,” Ted said. “A lot of kids from the projects play basketball in that park.”

“Well then how about Brittany Spears? We could get Wallace some of those big plastic tits and a shiny pink thong.”

“That’s not very original,” Ted said. “Everyone with a Brittany Spaniel has probably thought of that. Plus, Wallace doesn’t even look like enough of a Brittany to pass as one.”

Up ahead, we could hear that Wallace had flushed out a wild turkey. He let out a war cry and took off through the brush.

“It would be hard to keep a thong on him anyway,” I said.

Eventually—I don’t remember how—I came up with the idea of Dogatella Versace. It was the year Jennifer Lopez had worn that infamous, diaphanous, one-button dress to the Grammys.

Eventually—I don’t remember how—I came up with the idea of Dogatella Versace. It was the year Jennifer Lopez had worn that infamous, diaphanous, one-button dress to the Grammys.

I like to think that the idea came to me in one great creative burst; a flash in which I saw the complete outfit: Wallace in a mini J. Lo dress, with a long blonde Donatella wig, and his white fur tinted to Versace’s creepy shade of tan.

Eureka! My heart began to pound and the area behind my neck began to tingle, as it always does when I have tapped into The Universal Source.

There were two obstacles to expressing my creative inspiration, however. One was convincing Ted that his son needed to be swathed in Versace, and the other was finding someone to make the dress. Fortunately, we lived in New York City, the land of oddball specialists, so the latter was a piece of cake.

At any given moment, you could open up the Yellow Pages and find someone to sing opera to your geraniums while you traveled to Reykjavik; you could hire someone to sew mink to the straps of your seatbelts so that you wouldn’t chafe your chest. And you could find a handful of talented, expensive seamstresses who would custom make a dress for your dog. I found my doggie dressmaker, by providence really, on Manhattan Dog Chat. She just appeared one day in early September, answering a post from someone who had some extra upholstery fabric and wanted to make a little jacket for her “hard to fit” Maltese.

Immediately I called this woman and told her about my Dogatella Versace idea. “How big is your dog?” she asked me. And when I told her Wallace weighed seventy pounds she said, “Well, I usually only work with little dogs.” I felt myself getting defensive, and reverting into that hateful “Us and Them” mentality that, as a Buddhist, I try to not maintain: Us being big dog people (they are real dogs, after all) and little dog people.

Meanwhile, she was probably thinking I was insane for wanting a Versace dress for a 70-pound spaniel. A male spaniel with no effeminate qualities whatsoever. But because I was the customer, and because I offered to pay her a hundred bucks, we agreed that she would pick out some J. Lo-looking fabric and meet me at my apartment for a fitting the following week. “He’s really cute,” I said added at the end of our conversation, because Little Dog People love to use the word cute.

Ted wanted nothing to do with this. He tried to list all the reasons why I should not dress our dog in drag (i.e.: you’re humiliating him, you have better things to do with your time) but in the end he saw how excited I was about the project and how unwilling I was to back off. “When is she coming?” he finally said in resignation.

“Next Saturday. At three.”

“Well, I’ll just make sure I’m not around Saturday at three,” he said.

When Sheila, the dressmaker, arrived at the appointed hour, we were both relieved to find that we liked each other immediately. You never know with the Internet. She was a theater person, a costume designer, who made clothes for dogs on the side, because it was profitable, and because she loved dogs. “I used to have one,” she said, “but now I travel way too much.” As she talked, she measured Wallace’s ankles, and the length of his legs, and the distance from his neck to his tail. “Now, this will be the challenge,” she said, pointing at his privates. “We have to have the plunging neckline to mimic the dress, but it will have to fasten in front of his wee-wee. I’m just not sure it will hang right though.” She stared at Wallace thoughtfully, considering how his body would handle the complicated drapes of cloth, and I was glad Ted wasn’t here to witness this. The “wee-wee” comment would have sent him through the roof.

Wallace was a perfect fit model. I fed him liver treats throughout the whole process, so that he would stay still, and he didn’t try to lunge at Sheila when she leaned in too close to his head.

Wallace was a perfect fit model. I fed him liver treats throughout the whole process, so that he would stay still, and he didn’t try to lunge at Sheila when she leaned in too close to his head.

I was so proud of his behavior, and of his progress as a formerly abused dog, that I started to get teary-eyed. “You’re like the mother of the groom,” Sheila said. “Or the bride, as it were.”

“It’s just that,” I said, wiping my eyes, “he’s a shelter dog, and he was abused, and whenever I see him interact tenderly with new strangers I am just so grateful.”

“Now you tell me,” Sheila said. “But he doesn’t seem threatening. It’s usually the little dogs you have to watch out for.”

I agreed. “They’re assholes.”

“Would you like me to take a picture of the two of you when I come back to fit the actual dress?” she said.

We hugged when she showed me the material she’d selected. It was perfect: sheer, green, bold, in a tropical pattern that mimicked the actual dress. Then I showed her the wig I’d bought, which was made of human hair and had cost me $50. “We mustn’t mention costs to my husband,” I said.

“My lips are sealed,” she said.

Then I told her about the Three Headed Dog Man.

“We’ll kick his ass,” she said.

I gave her cash and we arranged to meet for a final fitting in two weeks’ time.

In the meantime, I got a call from one of my mother-in-laws, who said she was going to be coming to New York for a visit. I absolutely love visits from my mother-in-laws (I happened to be blessed with not one but two dynamite mother-in-laws, who liked me despite the fact that I never cooked for their son/step-son, never wrote or called, never produced any grandchildren, and talked non-stop about my dog). But this visit was scheduled for the weekend of Halloween. I faced a true conflict. My manners, upbringing, and sense of general decency suggested that I should scrap the Halloween contest and act like a proper hostess. My mother-in-law was a sharp, sophisticated woman who, when she visits the city, likes to spend her time good restaurants and sample sales. But I’d already invested all that money into Wallace’s dress, and I couldn’t get the smug face of the Three-Headed-Dog man out of my head. “Do you think I could talk you into going with me to a doggie Halloween contest?” I asked her on the telephone. “It might be fun.”

“Sure,” she said. “We can do anything you want.”

Her graciousness did not put me entirely at ease, however. I worried that I was taking a risk with my reputation with that half of the family. In fact, years later, when Ted and I got divorced, I wondered if that particular weekend continued to come up in conversation, when the family sat around the dinner table discussing “signs.” As in, “we always knew that marriage wouldn’t work out; why, think of the time she forced her dog to enter a Halloween contest….”

Anyway, the big day of the contest arrived and I was nervous. My mother-in-law, had arranged to meet me at Tompkins Square Park so that she could do some shopping beforehand, and Ted had decided not to come at all. “I have to work,” he said, which I noticed was something he had to do whenever I had Wallace in costume.

He had to work on St Patrick’s Day, when Wallace wore a headband with sparkly shamrock antennae. He had to work on Easter (bunny ears) and the Fourth of July (flag hat). He was a hard worker, Ted, and that morning he apologized to Wallace for not being able to spend the day with him. “Someone had to pay for all your food,” he said. “And your clothing.

I was busy combing Wallace’s wig out. Then I combed my own hair.

When Wallace and I got to the park, the sky was overcast and the day was humid—an uncommon phenomenon for October. I was wearing a turquoise vinyl jacket to match Wallace’s costume, and the vinyl made me sweat. This for some reason made me cranky, and it was a mood I couldn’t shake. The whole vibe of the contest was off that year. Maybe it was the humidity, maybe it was me, but the dog run seemed less festive; less crowded. “There’s another doggie parade this year over in Chelsea,” someone told me. “All the drag queens are over at that one, I’m sure.” I felt a bit dejected by this—once again something better was happening someplace else, where I was not. And the best place to be is always Where the Drag Queens Are.

But then I got a good look at some of the costumes and felt better again. There was a Corgi transformed into a Hoover. There were two baby cocker spaniels dressed as a bride and groom. Then the Three-Headed Dog man entered the dog run and Butterscotch was dressed up as—get this—Dogzilla. I could hear Ted say, “How unoriginal,” and I couldn’t help but smile. Sure, it was a spectacular costume—he had created a twelve-foot, elaborately airbrushed Styrofoam tail, with spiky fins, savage scales, and moveable parts. But please. Even Aunt Mabel in Idaho could have come up with Dogzilla.

But then I got a good look at some of the costumes and felt better again. There was a Corgi transformed into a Hoover. There were two baby cocker spaniels dressed as a bride and groom. Then the Three-Headed Dog man entered the dog run and Butterscotch was dressed up as—get this—Dogzilla. I could hear Ted say, “How unoriginal,” and I couldn’t help but smile. Sure, it was a spectacular costume—he had created a twelve-foot, elaborately airbrushed Styrofoam tail, with spiky fins, savage scales, and moveable parts. But please. Even Aunt Mabel in Idaho could have come up with Dogzilla.

Two years had passed since The Happy Camper had faced the Three-Headed Dog. And Wallace was a completely different dog by this point. He was happier, and better adjusted, and the dog run no longer meant “defend thyself” to him; it meant Play. So the minute I took his leash off inside the dog run, he took off after a Border Collie and the two of them ran like mad. “Wallace!” I shouted. “Your dress! You’re ruining your dress!”

I told him to come but he wouldn’t listen to me. It took fifteen minutes to finally cornered Wallace and put him back on his leash. “Now stay still,” I said to him. “Sit!” His wig had been thoroughly dragged across the ground and was now tangled with woodchips and leaves. I told Wallace he was the worst dog in the world.

My mother-in-law showed up just as I was shouting at my dog about the state of his long blond hair. She waved to me from beyond the fence. Only dogs and their guardians were allowed in the run. I blew her a kiss and smiled. Wallace’s wig kept slipping off, and every time he moved his dress would shift sideways, and he’d step on the hem with his back paws. “Stay still!” I snapped at him. “When I tell you to sit, you sit!” There was irritation in my voice, and I looked around to see if anyone had heard.

The registration was about to begin. Butterscotch and his guardian sat placidly in line, both confident that they would win the contest.

Meanwhile, the Border Collie kept running up to us and biting at Wallace’s wig. “Go away!” I said to her, and to Wallace: “Stay still! When I tell you to sit, you sit!” But poor Wallace wanted to play with the Border Collie. He wanted to stalk squirrels. But I was convinced the whole “effect” of his dress would be ruined if he even lifted his leg to pee. So every time he tried to get up from his sit, I’d apply pressure on his shoulders and push him back down.

Years ago, I’d worked at a children’s fashion magazine and one of my jobs was to assist the art director on photo shoots. Once a month, stage mothers would arrive with their stiffly coiffed sons and daughters. I remember my shock the first time I saw a toddler girl wearing makeup and four-inch heels. Her hair had been curled a la Shirley Temple, and she was unhappy that day—perhaps because of the shoes. But her mother was even unhappier. She kept insisting to me that Kelly normally didn’t act so ornery, that Kelly knew how to be a good girl. “She’s just being very bad today,” the mother kept saying loudly and bitterly “Very bad.”

Years ago, I’d worked at a children’s fashion magazine and one of my jobs was to assist the art director on photo shoots. Once a month, stage mothers would arrive with their stiffly coiffed sons and daughters. I remember my shock the first time I saw a toddler girl wearing makeup and four-inch heels. Her hair had been curled a la Shirley Temple, and she was unhappy that day—perhaps because of the shoes. But her mother was even unhappier. She kept insisting to me that Kelly normally didn’t act so ornery, that Kelly knew how to be a good girl. “She’s just being very bad today,” the mother kept saying loudly and bitterly “Very bad.”

Now the line of dog-contestants moved, and Wallace stood up without permission and stepped on the hem of his dress. “Sit!” I snapped at him.

Then, suddenly, I saw myself: angry, snappy, perfectionist, dissatisfied.

I had become a stage mother. I had put my own needs before my child’s.

When the beginning of the contest line-up was announced, I couldn’t even look at my mother-in-law. I thought she might see the shame on my face and I didn’t want to see it on her face too.

The crowd roared with laughter when Wallace was introduced as Dogatella Versace, and they cheered madly when, later, he won first prize. Last year first prize had been a six-month supply of California Natural and a CD player; this year it was a $40 gift certificate to a new pet store. When we went up to the stage to take the prize, the judge hung a “Best in Show” medal around Wallace’s neck. It was brass with a red white and blue ribbon that made him look like an Olympian. As the crowd clapped and cheered, a newspaper reporter snapped our photograph, but I refused to tell him my name. I, who for years had told myself I had sought the spotlight, was suddenly ashamed.

As soon as the contest was over I took the medal off Wallace’s neck. Then I took off the dress, and the wig. “You were such a good boy today,” I told him, and then I knelt down and apologized for the beastly way I had behaved. “I’ll never put you through that again,” I told him. “I won’t even make you wear a birthday hat if you don’t want to.”

And so far, my promise has been good.

The medal still hangs on Wallace’s bulletin board, which hangs above his “feeding station.” I’d like to think he notices this medal every time the bowl of ground turkey and boiled potatoes is set down before him, and that he somehow feels wistful, or proud, but mostly he just gobbles his food rapidly. Grateful, perhaps, that he isn’t being forced to wear a wig.

-- Lee Harrington is the Author of *Rex** and the City: True Tales of a Rescue Dog Who Rescued a Relationship. *“Hands-down the best human with dog memoir you'll ever read!"