Ever wonder what it would be like to marry a man who grew up in a palace? I did exactly that when I wed Ajay Singh, a fellow journalist who had grown up in Old Delhi and the Himalayas. Throughout the 1990's, I even lived for weeks at a time behind the rusted wrought-iron gates of the Singh family's one-hundred-room Indian palace.

Ever wonder what it would be like to marry a man who grew up in a palace? I did exactly that when I wed Ajay Singh, a fellow journalist who had grown up in Old Delhi and the Himalayas. Throughout the 1990's, I even lived for weeks at a time behind the rusted wrought-iron gates of the Singh family's one-hundred-room Indian palace.

Ajay and I met when we were both worked at Time Inc.'s newsweekly Asiaweek in Hong Kong. Although I knew very little about my fiancé or his family background, we still got engaged within three months of meeting at a company offsite event. A few months after this engagement, I discovered that not only did Ajay grow up in a rambling old 19th-century grand manor on the outskirts of Delhi, but also that we were now set to inherit the grandest wing of the house.

It may sound like a fairytale but, of course, there's always the fine print. Mokimpur - as the house is called - turned out to be not much of a fantasy palace. Believe me, it was no luxurious showcase of velvet daybeds, gilt-framed portraits of maharajas and other lofty ancestors, and sweeping palm-dotted landscapes. Instead, it was more of a sprawling moldy tear down, with hot-and-cold running mosquitoes, belligerent peacocks, and the odd royal ghost or two.

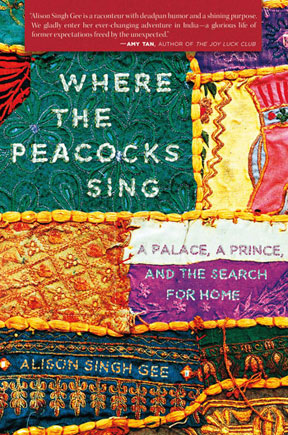

I write about my adventures - or misadventures - in my new memoir,Where the Peacocks Sing. Of course, any relationship with India is also a relationship with its food -- its mouth-watering curries, kormas, pakoras and parathas -- and I was privileged to be able to watch two amazing Indian chefs at work -- namely, Mrs. Singh and her beloved family servant Hoti Lal.

Here's a peek into the book, followed by Hoti Lal's top-secret recipe for the best chai on the planet. Namaste and enjoy!

Fear of Flying

I never knew peacocks could fly.

I never knew they could do much of anything. As a child growing up in Northeast Los Angeles, I only ever saw them at the botanical gardens in Pasadena or roaming the zoo. They were stunning birds, with their built-in tiaras and show-off coloring. But let’s face it: They seemed pretty useless. Waddling across manicured lawns, admiring flowers, plopping their fat stomachs onto grassy patches in the shade, these pampered birds only broke a sweat when the garden groundskeeper rang the dinner bell. Peacocks were charming but relatively pointless, flashing their plumage like a socialite working her best fur and jewels, and that’s all.

Or so I thought.

My understanding of peacocks was about to take a quantum leap.

I was sitting on the terrace of a palace in India. This was not some trussed-up five-star hotel in a commercialized Indian city, lousy with Patagonia-clad tourists. This was the ancestral home that had belonged to my fiancé Ajay’s family for the past century, and it was the kind of regal spread you’d find in a Merchant Ivory film—huge, awe-inspiring, and vibrating with legacy. The house stood like a porcelain deity in the middle of a lush and flowering village called Mokimpur, which is also the name the Singh family gave the house. Ajay had spent much of his childhood at this magnificent residence, playing hide-and-seek in its hundred rooms, racing his village friends along the river, and jumping into the deep, cool reservoir when the summer heat became unbearable.

With its fragrant mango groves, silent skies, and choruses of songbirds and screeching parrots, Mokimpur was about as different from my hometown as the moon. Later, when I looked at a globe and placed my finger on Northern India, I realized that Ajay’s tiny village sat almost literally on the opposite side of the sphere from where I grew up. But it’s not like I needed a map to tell me what I already knew in my heart.

As an American journalist based in Hong Kong, my life was anything but placid, predictable, or comforting. My cell phone buzzed every two minutes; I had a half-dozen deadlines to meet every day, and a whirling social world that included lots of good friends (most of whose last names I somehow never quite learned). Hong Kong, the futuristic gateway to the East, had skyscrapers instead of trees, subway platforms instead of terraces, daredevil taxis instead of slow-moving yaks. Lunch was often a bowl of noodles eaten standing up; dinner, cocktail party hors d’oeuvres and a lethal gin and tonic. (Breakfast wasn’t actually in my vocabulary—I usually jumped out of bed at the blast of the alarm clock, wriggled into a dress, strapped on some heels, and dashed out the door.) In this insanely built-up, inhumanly crowded place, where apartment towers seemingly sprang up overnight like bamboo, the locals liked to say that the national bird was the jackhammer.

Not so in Mokimpur.

It was my first week in India. Ajay and I were idling over steaming cups of chai and plates heaped with mouthwatering veg pakora, deep-fried cauliflower, onions, potatoes, and carrots with a spiced, crispy coating. Three servants dressed in kurtas and loose cotton pants ferried about filling teacups and delivering fresh chutney and hot samosas. As Ajay and I lounged on the veranda, I watched dozens of wild peacocks, shrieking with glee as they glided from mango tree to neem tree, streaking the sky with their over-the-top rainbow colors.

Peacocks, not jackhammers, are the national bird of India. Here they were almost unrecognizable to me, not at all like their L.A. cousins. Indian peacocks were tenacious and fierce, agile and vocal. Roaming wild in the villages, these birds were just like the people—warriors in the primordial battle for survival. I watched them in the middle distance and shook my head. “All this time I thought they were ground dwellers,” I said to Ajay. “Who knew these humongous things could jet through the trees like that?”

“This is India,” Ajay said. “We do whatever we need to do to survive—if that means flying, we fly.” He took a sip of his chai and tilted his head. “An Indian peacock can kill a baby cobra in thirty seconds flat. Their beaks are laser sharp. Before the snake knows what’s happened, it’s been sliced into a pile of sashimi.” He looked dashing in his white kurta pajama suit, and worlds apart from any man I’d ever dated.

From Where the Peacocks Sing by Alison Singh Gee. Copyright © 2013 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

CHAI TEA FOR TWO

Hoti Lal, who has been the Singh family servant for fifty-four years, makes the most amazing cup of chai -- somehow he always creates layers and layers of spices and textures in each cup.

I've managed to sneak the head servant's recipe out of the haveli. Here it is, friends. And, oh yeah, don't be afraid of using whole milk. Hoti Lal sure isn't.

Ingredients:

Water

Indian Black tea (we get ours by the bagful at India Sweets & Spices)

Fresh ginger

Whole milk

Organic honey

Cardamom in the pod (but powdered will do)

Cinnamon sticks

White pepper

Boil three cups of water. Peel a thumb-sized piece of ginger and finely grate and boil in the water. Add two heaping tablespoons of Indian black tea (five tea bags will do). Pour in one cup of whole milk, or as much is needed to make the tea turn a caramel color. (Hey, worry about the calories later. Good chai has body and only whole milk can give that). Lower the heat to medium and take care to let the mixture boil through (but *not* boil over).

Crack ten pods of cardamom and grind the seeds. Pour the ground cardamom powder into the pot. Throw a cinnamon stick in for good measure. If you like a little bite in your chai, add several shakes of white pepper.

Pour the tea and milk mixture into two big mugs. Lace each cup with at least one dripping tablespoon of honey (more if necessary -- and more is always necessary in our house. Ajay equates honey with a flow of positive emotion, and so his chai is super sweet). Stir thoroughly and serve with love. In the garden -- that's always a nice touch.