This is a story about Beef Stroganoff. But before your mind wanders to sour cream and Russian Tzars, picture the small kitchen in which it was created. Probably 9 by 9, with a rudimentary stove, a wooden counter which doubled as a chopping board, a hatch leading into a dining room, a single sink with a window facing onto the mountain, with the silver birch trees, where the blueberries and wild strawberries grew in the summer. The larder, where on special occasions gravlaks was made (weighed down with wooden boards and round lead sinkers), was reached via a trap door in the wooden floor, the entrance covered by a red and white rag rug.

This is a story about Beef Stroganoff. But before your mind wanders to sour cream and Russian Tzars, picture the small kitchen in which it was created. Probably 9 by 9, with a rudimentary stove, a wooden counter which doubled as a chopping board, a hatch leading into a dining room, a single sink with a window facing onto the mountain, with the silver birch trees, where the blueberries and wild strawberries grew in the summer. The larder, where on special occasions gravlaks was made (weighed down with wooden boards and round lead sinkers), was reached via a trap door in the wooden floor, the entrance covered by a red and white rag rug.

Because this story takes place a long time ago, when I was just a small child, the details of the preparation of the stroganoff are hazy. In those days such things did not interest me, and although no doubt many conversations were had by the grown-ups in the family about which butcher had the best meat as it was a special occasion -- and just on that day money didn't seem to matter quite as much -- I think I may have been sitting on the roof of the wooden outhouse, picking black morello cherries and stuffing them into my mouth at the time.

I did know that when the meat did arrive -- via my grandfather's dark red Lancia with its sweet-smelling leather seats -- there was a great welcoming party consisting of my grandmother, my mother, my aunt, maybe even my father in his rolled up jeans and a fish bucket, having coincidentally just stepped off the boat after a morning of catching cod and mackerel in the days when cod were as bountiful as the little crabs under the jetty. My grandfather was in his city clothes, his doctor clothes. The dark grey wool trousers, the pale blue shirt, the elaborately polished brown loafers he wore in Oslo. He carried the special stroganoff beef in front of him, laying it on his two hands like a tray, wrapped in white butcher paper and tied with twine. He had a smile on his face.

"The first element of our most excellent feast has arrived" he said.

While the women grabbed bags of carrots and mushrooms, punnets of strawberries, glass bottles of cream from the back of the car, he lead the way up the hill, winding up the rocky path, under the oak tree with the bell on it, past where the raspberries grow, to find a cold place for beef in the ice box. By now, the children had come to find out what the fuss was about, and waited patiently, faces stained cherry-red, but grinning, to see whether a box of ice cream cones had made it into the loot.

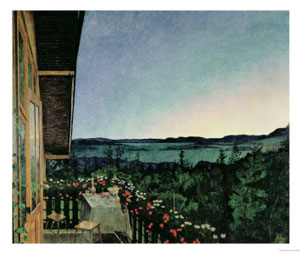

Much fuss was made of the table. In our family, the table is laid even a day in advance of a big party. My mother says it makes her feel organized. Linens from long ago, laundered and starched and folded in an M shape, were brought down and re-ironed and laid on the table, which looked unfamiliarly large with its leaves added. The old bone-handled silver, which was never used in the summer on the island, was brought out and polished. Wildflowers were gathered; candlesticks were cleaned with boiling water and new candles placed in them. A Christening dress was threaded with blue silk ribbon at the throat and wrists because it was a boy that would be baptized in the morning. Cheerfully atheist Lutherans brought suits out to press, shirts to iron. My uncle was to sweep the terrace. Long boxes of nasturtiums were watered, roses pruned, vines cut back off the apple tree, a hammock put away in the wood shed.

Much fuss was made of the table. In our family, the table is laid even a day in advance of a big party. My mother says it makes her feel organized. Linens from long ago, laundered and starched and folded in an M shape, were brought down and re-ironed and laid on the table, which looked unfamiliarly large with its leaves added. The old bone-handled silver, which was never used in the summer on the island, was brought out and polished. Wildflowers were gathered; candlesticks were cleaned with boiling water and new candles placed in them. A Christening dress was threaded with blue silk ribbon at the throat and wrists because it was a boy that would be baptized in the morning. Cheerfully atheist Lutherans brought suits out to press, shirts to iron. My uncle was to sweep the terrace. Long boxes of nasturtiums were watered, roses pruned, vines cut back off the apple tree, a hammock put away in the wood shed.

My grandmother started her stroganoff early in the morning with only seagulls for company. French jazz songs played low on the radio, and wearing one of her inimitable house dresses, the ones saved only for the island, perhaps the zebra striped bathing dress with the tight bodice and the turquoise underskirt, and a red chef's apron with the words "Coffee, Tea or Me?" on the front, she locked herself in her small galley with a large pot. We woke up to the smell of onions caramelizing slowly in butter with a little thyme and the sizzle as the temperature was raised and the thin strips of beef thrown in. "This beef is good enough for tartare" she had said to my grandfather when she inspected it the day before and he smiled proudly knowing he'd done his part well.

I can't remember if we were forced to swim in the sea that morning to make sure that we were clean for church, or whether we were compelled to leave the house because the smell of the unctuous, sweet and salty stew was making us crazy with hunger, but the Oslofjord was ice cold that day (my brother being a reliable barometer for such things by the shade of his lips).

Church smelled like dust and old overcoats. The vicar spoke in monotone old Norwegian that I couldn't understand and the hymns, which were always my favorite part of church, were unfamiliar and therefore impossible to sing along to. I thought about how much more jolly the whole thing would have been with a rousing chorus of "Guide Me O Thou Great Redeemer." But the baby didn't cry when the water was poured on his head. It was probably warmer than the Oslofjord. Everyone said what a good boy he'd been.

Church smelled like dust and old overcoats. The vicar spoke in monotone old Norwegian that I couldn't understand and the hymns, which were always my favorite part of church, were unfamiliar and therefore impossible to sing along to. I thought about how much more jolly the whole thing would have been with a rousing chorus of "Guide Me O Thou Great Redeemer." But the baby didn't cry when the water was poured on his head. It was probably warmer than the Oslofjord. Everyone said what a good boy he'd been.

Glasses of champagne were handed out to the guests who'd followed us home. My aunt had made tiny little open sandwiches with shrimps and mayonnaise and dill, the size of postage stamps. There were brown-bread ones too, topped with gravlaks and mustard sauce, and even little slices of egg with lumpfish caviar and sour cream. The kitchen was steamed up with the smell of the stroganoff even though the window was open. It bubbled away gently on the stove in a huge, copper pot, a beautiful pink color. When we were confident that the grown-ups were sufficiently ensconced in conversations with long-missed relatives, my brother and I snuck in, dragged a stool over to the stove, and I climbed up on it. Waving my hand over the pot, so that the divine smell would waft into my nostrils, I closed my eyes. It was the most delicious smell in the world.

"Hand me a teaspoon, quick, before they find us" I said to my brother, and as I had seen my mother do, dragged the little spoon across the surface of the stew to scoop up some of the sauce. I blew on it and handed it to my brother to taste.

"Hand me a teaspoon, quick, before they find us" I said to my brother, and as I had seen my mother do, dragged the little spoon across the surface of the stew to scoop up some of the sauce. I blew on it and handed it to my brother to taste.

"I have died and gone to heaven" said my five year old brother, dramatically. He handed the spoon back to me so that I could taste it. I scooped, blew hard on it and put the spoon up to my lips. It was sweet and the sourness of the tomatoes had completely gone. It was a little peppery and creamy too, thick from simmering, and the flavor of the beef, cooked with the onions and thyme, was like salty toffee. I held it in my mouth for as long as I could bear to, like a sommelier, wanting that flavor to ooze into every pore. We took it in turns to watch out for the grown ups, who were laughing loudly outside, and dip our spoons into the scrumptious pink sauce.

One would imagine that beef stroganoff would be served with egg noodles. But this was Norway in the summer on our little island. And besides, my grandmother made up her own rules for everything. The stew was served with buttery long-grain rice, and sprinkled with finely chopped parsley, which my grandmother liked to put on most things, except herring, of course.

No-one seemed to notice what we'd noticed. They were grown-ups and they'd learned long ago not to talk too much about the food, as was the custom of the country. They toasted the baby boy with some very good claret that my grandfather had brought down from his cellar in Oslo. It was, they said, a marvelous day, a day to remember. The baby gurgled and smiled at strange aunts and uncles and my brother and I had our picture taken with him in his Christening robe, which we'd both worn previously, threaded with different ribbon. We hid our teaspoon outside the kitchen door so that no-one would know about our secret feast. Actually, we buried it, next to the chives, where we thought no-one would find it.

Bumble Ward is a blogger and writer living in Los Angeles. She grew up with a Norwegian mother and an English father and spent every summer on an island in the Oslo fjord. www.misswhistle.com