This is an excerpt from the book "Clothing Optional: And Other Ways to Read These Stories"

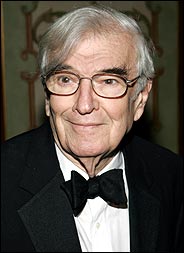

We had just started Saturday Night Live, I was an apprentice writer, 24 years old and I felt intimidated. Chevy was hysterically funny. So was John and Danny and Gilda and Franken. And Michael O’Donoghue, well, Michael O’Donoghue simply scared the shit out of me. So I stayed pretty much to myself. One day I came to work, and on my desk was a framed cartoon. A drawing – no caption – of a drunken rabbi staggering home late and holding a wine bottle. And waiting for him on the other side of the door was his angry wife, getting ready to hit him with a Torah instead of a rolling pin. I had no idea who put it there. I started looking around and out of the corner of my eye I saw a white-haired man in his office, laughing. He had put it there. That was the first communication I had with Herb Sargent– which was significant given that he never spoke and he gave me a cartoon that had no caption.

We had just started Saturday Night Live, I was an apprentice writer, 24 years old and I felt intimidated. Chevy was hysterically funny. So was John and Danny and Gilda and Franken. And Michael O’Donoghue, well, Michael O’Donoghue simply scared the shit out of me. So I stayed pretty much to myself. One day I came to work, and on my desk was a framed cartoon. A drawing – no caption – of a drunken rabbi staggering home late and holding a wine bottle. And waiting for him on the other side of the door was his angry wife, getting ready to hit him with a Torah instead of a rolling pin. I had no idea who put it there. I started looking around and out of the corner of my eye I saw a white-haired man in his office, laughing. He had put it there. That was the first communication I had with Herb Sargent– which was significant given that he never spoke and he gave me a cartoon that had no caption.

I had seen him years before. Or at least I think I did. When I was a kid. My father manufactured jewelry and he had his shop on 52nd Street between Fifth and Madison. I used to come into the city from Long Island and run errands for him during the summer. And no matter where the delivery was supposed to go, I made sure I got there by going through the lobby of what was then called the RCA Building, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, with the hopes that maybe I would see Johnny Carson (whose show was upstairs) or some of the people from That Was the Week That Was: Buck Henry, Bob Dishy, David Frost – or Herb Sargent, who was the producer. I knew his name from the credits. As a young boy who wanted to be a TV writer some day, this was like hanging around outside of Yankee Stadium waiting to see the players going through to the clubhouse.

I had seen him years before. Or at least I think I did. When I was a kid. My father manufactured jewelry and he had his shop on 52nd Street between Fifth and Madison. I used to come into the city from Long Island and run errands for him during the summer. And no matter where the delivery was supposed to go, I made sure I got there by going through the lobby of what was then called the RCA Building, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, with the hopes that maybe I would see Johnny Carson (whose show was upstairs) or some of the people from That Was the Week That Was: Buck Henry, Bob Dishy, David Frost – or Herb Sargent, who was the producer. I knew his name from the credits. As a young boy who wanted to be a TV writer some day, this was like hanging around outside of Yankee Stadium waiting to see the players going through to the clubhouse.

And now, now I was actually working with Herb Sargent. We gravitated toward each other (or should I say I forced myself upon him?) because my background was in joke writing and he was basically in charge of Weekend Update, which was all about jokes. So I found my way into his office and we would go through the newspapers together and write jokes for Update. We made each other laugh. The silence was comfortable. And over time, the relationship grew deeper.

I believe that you choose people to fulfill roles in your life. And I cast Herb in the role, not only of mentor but – there’s a Jewish expression called tzaddik. If someone’s a tzaddik, it means that they’re “just.” That they embody wisdom and integrity. I cast Herb in that role. He was the oldest person I knew, and I treated him with the kind of respect usually reserved for people who symbolize a person’s private definition of truth – to the point where he was the one guy I knew that I couldn’t lie to. And as the show became more successful and I started making a little money, he was the only one I didn’t do drugs in front of. Still later on, when I was having problems with a girl I was going out with, I went to Herb, who was married 34 times, for advice.

I believe that you choose people to fulfill roles in your life. And I cast Herb in the role, not only of mentor but – there’s a Jewish expression called tzaddik. If someone’s a tzaddik, it means that they’re “just.” That they embody wisdom and integrity. I cast Herb in that role. He was the oldest person I knew, and I treated him with the kind of respect usually reserved for people who symbolize a person’s private definition of truth – to the point where he was the one guy I knew that I couldn’t lie to. And as the show became more successful and I started making a little money, he was the only one I didn’t do drugs in front of. Still later on, when I was having problems with a girl I was going out with, I went to Herb, who was married 34 times, for advice.

As a native New Yorker, I was also drawn to Herb because, to me, Herb was New York. But an older, more romantic New York that took place in black and white like the kind of TV I grew up on and wanted to be a part of some day. Comedy with a conscience. And mindful of its power to influence. From the silly “Franco is still dead” jokes to softer ones about global warming, Herb taught us about the equal weight they carried.

When Lorne founded the show, he said that our generation was not being spoken to on television. So the politics on SNL were addressed to our generation – the baby boomers who had grown up watching television and went to Woodstock and thought it was absurd how Gerald Ford fell down so much. But here was Herb, a charter member of the older generation, who validated us. And encouraged us. And quite often led the way. What a curious hybrid he was – a man who was older than my father, at the same time younger than my Republican brother – who wasn’t trying to be preachy. Or controversial. But he lived in that place where he was writing about those things that he genuinely felt. Herb was grounded in his beliefs. So when he wrote, he wrote from within.

When Lorne founded the show, he said that our generation was not being spoken to on television. So the politics on SNL were addressed to our generation – the baby boomers who had grown up watching television and went to Woodstock and thought it was absurd how Gerald Ford fell down so much. But here was Herb, a charter member of the older generation, who validated us. And encouraged us. And quite often led the way. What a curious hybrid he was – a man who was older than my father, at the same time younger than my Republican brother – who wasn’t trying to be preachy. Or controversial. But he lived in that place where he was writing about those things that he genuinely felt. Herb was grounded in his beliefs. So when he wrote, he wrote from within.

And when I left New York and moved my family to Los Angeles, I knew my city was in good hands because Herb was here. And that I was still connected here because to know Herb Sargent was to be two degrees of separation from anyone on the planet. It was in his office that I’d met Mort Sahl and Herb Gardner and Art Buchwald and Avery Corman and Ed Koch and Bella Abzug. So in my mind, even though I was now living a full continent away, all I had to do was call Herb, remind him that I disliked L.A. as much as he did, and I was home. It was as simple as that – and all he asked in return was that I not join the Writers Guild, west.

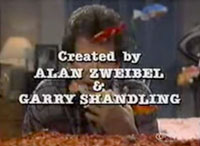

So our relationship continued long distance. I still tried hard to please him. Make him proud. I sent him a copy of anything I wrote or produced. Poor Herb, I actually sent him 72 videotapes of It’s Garry Shandling’s Show because his neighborhood didn’t get Showtime in those years. I also sent him first drafts of plays, movies, magazine articles and manuscripts for books. He’d call and give me notes. And in those pre-Internet days he’d send reviews from New York papers. “Did you see this one about the Jon Lovitz special you did? Congratulations,” he’d write. And whenever I’d get a bad review, he’d say, “Don’t read Time magazine.”

So our relationship continued long distance. I still tried hard to please him. Make him proud. I sent him a copy of anything I wrote or produced. Poor Herb, I actually sent him 72 videotapes of It’s Garry Shandling’s Show because his neighborhood didn’t get Showtime in those years. I also sent him first drafts of plays, movies, magazine articles and manuscripts for books. He’d call and give me notes. And in those pre-Internet days he’d send reviews from New York papers. “Did you see this one about the Jon Lovitz special you did? Congratulations,” he’d write. And whenever I’d get a bad review, he’d say, “Don’t read Time magazine.”

But after awhile, for some reason, I lost touch with Herb. I’m not sure why. He may have been mad at me. I’m not sure of that either. For some reason I never asked. Never called to clear the air or simply reconnect. Years passed. Until I saw him at the memorial of a former SNL associate producer. Herb had been sick and now looked, well, now looked his age. It threw me. He never looked his age.

I moved my family back to New York and started calling him again. Tried to jumpstart a friendship, make up for lost time. Calls were returned – but not as quickly as they once were. I misjudged the situation and took it personally. Figured it to be nothing more than the vestiges of our estrangement. A sign that things between us were not yet back to where they were. But I was determined to remedy that. I wrote a novel. And when it came time to submit the names of people on the acknowledgments page, I mentioned Herb and tried my best to figure out how and when I would let him know about it. Should I send him the galleys and have him come across it? No, too much had transpired for me to give him that kind of homework. Should I call and tell him? Let him know outright how grateful and indebted I felt? No, I knew that would only serve to embarrass him. Make him blush. Herb hated recognition. Hated blushing. So I waited. Decided to send him the published product once it came out and put a bookmark in the page that his name was on. It proved to be yet another miscalculation on my part. Herb died about a week before I had the chance to do so. I never got to tell him how much he meant to me. Somehow, some way, I hope he knows.

An original Saturday Night Live writer, Alan Zweibel collaborated with Billy Crystal on his Tony Award winning play "700 Sundays". Most recently, Alan's novel, "The Other Shulman" won the 2006 Thurber Prize for American Humor.