For more than 20 years, my dad, Howard Johnson, owned a very popular restaurant on the Upper Westside of Manhattan called the Cellar. The Cellar was a special place and at the time of its inception in 1973, there were very few, if any, black-owned restaurants outside of Harlem below 110th street. Ironically, my father bought the Cellar from another Black man, who owned it for a few years but decided to sell after having lost his appetite for the place. Despite its location in a multi-ethnic neighborhood, the clientele had become “too Black” for him.

For more than 20 years, my dad, Howard Johnson, owned a very popular restaurant on the Upper Westside of Manhattan called the Cellar. The Cellar was a special place and at the time of its inception in 1973, there were very few, if any, black-owned restaurants outside of Harlem below 110th street. Ironically, my father bought the Cellar from another Black man, who owned it for a few years but decided to sell after having lost his appetite for the place. Despite its location in a multi-ethnic neighborhood, the clientele had become “too Black” for him.

In the early ’70s, my father was working for Paul Stewart a well-known men’s clothing store and hanging out at some of the popular watering holes of the day, Vic and Terry’s, Jocks and Teachers, among others. Those that knew my dad would be quick to agree he had great taste, and a certain social prowess, easily mixing in any group. This combination made him a natural for his new venture as a restaurateur.

To say my father was a risk taker would be accurate, both in his private life—he married my mother Phyllis Martha Notarangelo, an Italian woman, when interracial marriage was still illegal in most states—and in business, where he jumped head first into an industry that other than a fondness for Jack Daniels, he had no experience in.

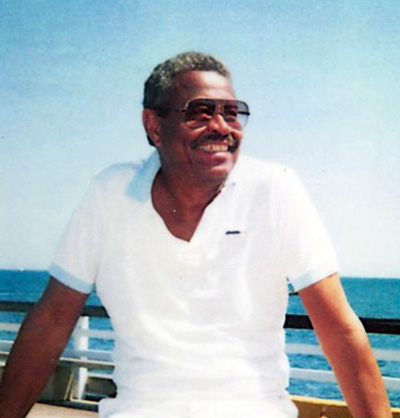

My father’s generation (he was born in 1925) was truly amazing. I’m so proud that my dad served as a Marine in World War II, where he witnessed and experienced prejudice around the world and at home, and yet never allowed any of it to detour him from blazing his own trail. He amassed a range of friends of all ages and races. His eye for style, a great suit, and the importance of good fabric, furniture (I still have the Eames chair he purchased 50 years ago), and cars made him memorable to so many. Jazz was a major love. He would fall asleep almost every night with the radio tuned to the local jazz station. My dad was happiest cruising in one of his cars on Martha’s Vineyard where he had a home, top down, listening to Miles Davis. He would often say “I wouldn’t want to leave here to go to heaven.”

The Cellar was a few steps down from street grade, dimly lit and had 8×10 black and white photographs of jazz greats lining the walls. There was a small stage that often held way more musicians than it was intended to, a long L-shaped bar, a 46 seat dining room, and a juke box. The crowd epitomized the “Black is Beautiful” slogan of the day. People such as Susan Taylor, Editor of Essence magazine, Ed Bradley, Arthur Ashe, Bill Cosby, Phyllis Hyman, Muhammad Ali, Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson, Diahann Carroll, Stevie Wonder, Miles Davis, Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, as well as hustlers, number bankers and State Supreme Court judges were friends and customers. My dad had his crew too, guys with names like Red, Bootsie, OT and Gopher—the list could go on. It would be accurate to say that, in its prime, the Cellar was the place for blacks to be.

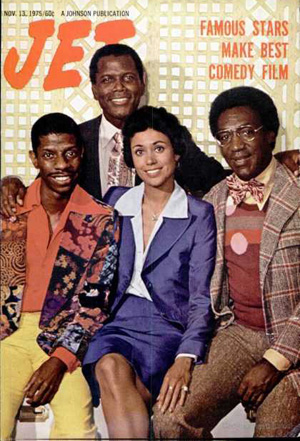

Every week while I was away at college, I would pick up a copy of Jet magazine at the campus center store and read bout my dad and the Cellar’s famous clientele.

Every week while I was away at college, I would pick up a copy of Jet magazine at the campus center store and read bout my dad and the Cellar’s famous clientele.

The first “chef“ Leroy—a very talented cook—was black and crazy as hell. A small, hot, very busy kitchen is not the best place for someone whose temper could flare at any perceived slight or mistake. My dad soon let Leroy go, or he quit (I don’t remember), and hired a tiny guy from Thailand named Woo. Woo took the soul food menu Leroy had created, that also had some typical pub grub found in many of the watering holes on the Westside like French Onion soup, Chef’s salad, and shrimp scampi and infused his own Thai touches. So the menu along with the above mentioned dishes had Thai beef salad, chicken gai yung. In Miles Davis’ book Miles, the Autobiography, he said the Cellar had “the best fried chicken in the world.”

Kenny Brawner’s band “Raw Sugar” would play three sets nightly to standing-room-only crowds. Songs from the Broadway smash The Wiz, like “Ease on Down the Road,” would bring the house down on a nightly basis. After the 3rd and final set at close to 4 a.m., with the crowd often wanting more, my dad would turn up the house lights while announcing, “You don’t have to go home but you can’t stay here!” The crowd would love it, taking the last sips from spilts of Moet or Lancers Rosé and head out into the early morning—happy, if not a little tipsy.

Though he may not have realized it at the time, not only was my father a trailblazer, he laid the foundation for me to follow in his footsteps. I learned about music, what to wear, how to carry myself, and pride of ownership. To this day people come up to me and talk about the Cellar and my dad.

Recently at Post & Beam one afternoon before we opened for business, an older gentleman came to the door. I let him in, thinking it was someone from the neighborhood who’d heard about the restaurant and was curious to see it. I thought he might be in his 80s, and though somewhat frail and a noticeable limp, he still had a swagger, plus his cap was tilted to the side just right. He took a close look at me and said, “You’re Howard Johnson’s son. I knew your dad from the Cellar,” We had a nice exchange and I considered offering him dinner on me, as he looked like things may have gotten a little tight. As I walked him outside we crossed the parking lot reminiscing, me trying to think of a smooth way to offer him dinner but not have it come off as if I didn’t think he could afford it on his own. Then he stopped for a moment to pull out his car keys to unlock his car—a brand new yellow Lamborghini.

He was just the kind of cat my dad would have known.

When my father passed in 2007, I called the New York Times to see about having his obituary printed in the paper. My father read the Times daily, and it wasn’t Sunday without the Sunday Times. The nice gentleman from the Times told me because they couldn’t find anything written about my dad to verify the facts in his obituary, and subsequently wouldn’t be including his passing in the paper. My good friend David Rabin had taken up the task of gathering the facts about my dad and wrote a wonderful tribute. Despite New York Mayor David Dinkins having given my father a proclamation for the years of operating the Cellar, the Times couldn’t confirm to its satisfaction who Howard Johnson was and what he and the restaurant meant to so many.

The sad truth is that even as recently as the early ’80s, the mainstream media rarely if ever covered black-owned restaurants. Certainly the absence of black food writers adds to the void. As such, many of the stories about black restaurateurs past and present will be told by writers who are unfamiliar with the challenges these operators faced then and now. With the recent passings of Elaine Kaufman of Elaine’s restaurant, the famous upper-Eastside watering hole, and Sylvia Woods, owner of Soul Food institution Sylvia’s, and the well-deserved coverage both deaths received, I’m reminded of my dad. He deserves to be remembered and will be by those who knew him.

Thanks to my dad, I still read the New York Times most days—and always on Sunday.

Brad Johnson is a veteran restaurateur who currently runs two Los Angeles spots, Post & Beam in Baldwin Hills and Willie Jane in Venice Beach.